By Remy Bargout

Environmentalists live under a growing and yet age-old illusion that the mainstream movement has gained a critical mass, or unstoppable momentum that ‘now, consumer society, world leaders, and the capitalist system must reckon with’. In reality, the mainstream movement does not speak to power, but actually exerts it. Elite environmentalism is a problem for many reasons but, perhaps most of all, for exclusionary factors of age, sex, and race.

In 2006, the UK Environment Agency asked a panel of experts to list the ‘top 100 people who have done the most to save the planet’. I have no idea who these experts were, but their list ranks Arnold Schwarzenegger #29 and Thomas Malthus #33 before Jane Goodall #48, David Suzuki #35, and Buddha #92. The top 20 environmentalists on this list include 1 landless peasant and 3 women (two of whom were the only persons of colour). As far as the Evening Standard is concerned, 8 of the ‘top 10 environmental influencers’ to follow on Instagram are white women.

Whether we speak of power, privilege, class, race, sex, or age – they overlap and intersect. However, if you look at the majority of environmentalists that the western world chooses to sensationalize and celebrate, the outcome is that environmentalism is elitist. Moreover, despite all the post-human and eco-loving good intentions of elite celebrity environmentalists, (western) environmentalism is pretty sexist and racist.

In his article, The environmental crisis is a moral challenge, not just a practical one, the Executive Director of Nature Canada, Graham Saul, described environmentalism as, “blanketed by a kind of ethical fog that prevents many otherwise well-intentioned people from seeing a burning injustice before their very eyes.” The article was a media piece for the report, Environmentalists, What are we fighting for?, written by Saul for the Metcalf Foundation.

The supposed aim of the study was to identify common language among “leading environmentalists to better understand whether or not they agreed that words played an important role in past social movements, and to see what words and concepts they would use to sum up the goal of the environmental movement today.” It is contradictory how the article reprimands environmentalists for ‘discussing environmental issues in polite terms’ using a similar style of politeness.

Graham Saul and part of Nature Canada’s Staff. Source: Nature Canada

The premise of the study is based on an assumption that ‘leading’ environmentalists are affiliated with a reputable NGO, business, or public institution, and these particular environmentalists have some authority to speak on behalf of the entire environmental movement. As a result, there were clear disproportions in the study’s participants. I looked into the job title, province, age, and gender of all 116 names listed as key informants in the report. The majority of respondents were directors, CEO’s, politicians, lawyers, financiers, NGO founders, and other frequent ‘armchair environmentalists’.

The study did not involve many activists. Around two-thirds of respondents seem to hold top or high ranking positions in an environmental NGO or civil society group. Only five percent of respondents were outside the age of 30 to 70. The gender ratio of interviews was two women for every seven men. The same number of Americans and Europeans were interviewed as those from the Prairies, Maritimes, and Northern Canada combined, which represent almost half of Canada’s population. The study could thus be titled ‘What environmentalism means to me and 100 other important people.’ In this sense, it is an ‘armchair’ environmentalism.

Environmentalists assume armchair status by finding social utility (i.e. prestige, acceptance, avoided shame) from ‘green’ consumer and professional decisions, not considering that ‘sustainability’ is an often privileged and layered illusion we reproduce through our ‘green’ performances. The author and environmentalist Peter Dauvergne puts it directly: “Environmentalism of the rich does not have the innate capacity to aggregate into global-scale solutions or transform the political, economic, and societal structures causing overconsumption, extreme inequality, and ecological decay.”

The ‘moral’ origin of environmentalism is our age-old demand for status goods and services. We have all been guilty of armchair environmentalism at some point. We value the status quo of modern life and also value ‘the environment’. Even the ‘sustainable’ decisions in our lives involve resource consumption. We try and justify this by eating less meat, buying fair-trade stuff, or writing aggravated articles about the uninspiring research of public executives.

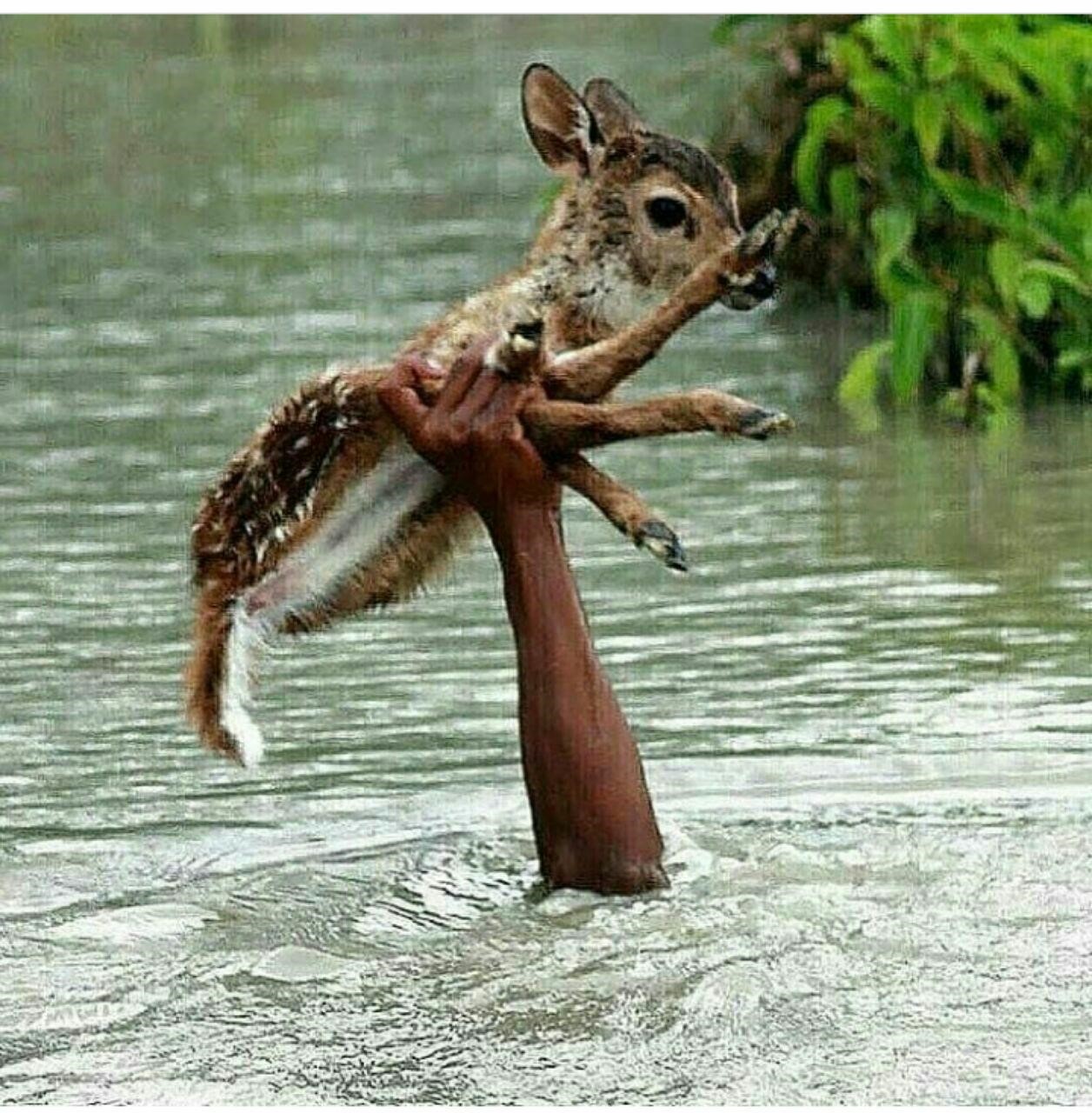

It is misleading to believe that environmental actions are inspired most by thoughts and words. Indeed, as Graham Saul and David Suzuki concluded in an earlier article: “Big changes often begin with simple local actions.” Real transformations are driven and inspired by individual deeds and everyday behaviour.

Boy saving baby deer during monsoon flood in Nijam Dupa, Bangladesh. Source: Gostaresh News.

So, what should environmentalists be fighting for? Action – and not morals, not symbols, not ideas about practicality – actual practicality. There are all types of environmentalists who would agree. More so, when acknowledging the diversity and complexity of any possible environmental ‘action’ in the world, a critical environmentalist interrogates the performances, time-places, group relations, power structures, and (among other things) privileges that substantiate all any type of environmental action or sustainable practice.

Environmentalism is not a metaphor and we should acknowledge that environmentalism (in varying degrees and contexts) is a diminishingly meaningful performance. Borrowing from Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s argument that decolonizationis not a metaphor, we could argue that when metaphor invades environmentalism, it kills every possibility of truly transformative changes. Saul’s study reinforces an illusion that we can improve ‘sustainably’ by writing, reading, and simply ‘caring about the environment’.

Timothy Morton explains that to be an environmentalist, “You don’t need to be a geostationary satellite or a scientist or an astronaut. Or a member of the UN or CEO of a global corporation.” Morton uses Naomi Klein’s description of global warming, “Climate change is slow and we are fast. When you are racing through a rural landscape on a bullet train, it looks as if everything you are passing is standing still: people, tractors, cars on country roads. They aren’t of course. They are moving, but at a speed so slow compared with the train, that they appear static.”

Jane Goodall puts it in even clearer terms, “We have to get together and take action now, and we have to understand that each single one of us, although we may feel helpless and hopeless as one person in a rather dark world, nevertheless, we have to realize that every individual makes a difference… and when hundreds, thousands, millions and hopefully billions of us make ethical choices then we start moving towards a better world.”

Part of the art by Hannah Stouffer in Timothy Morton’s book Dark Ecology.

In our attempts to be less polite and more critical, we need to avoid unethical and uncalculated historical comparisons between the abolition of slavery and environmentalism. Graham Saul’s article claims that environmentalists are fighting for ‘survival’ and compares them to abolitionists: “Even issues like slavery were primarily discussed in economic terms – as opposed to ethical – for hundreds of years. Recognizing this, it is not surprising that most of society today is still unable to appreciate the moral implications of climate change and mass species extinction.”

I sympathize with Saul’s sentiment that, “…we still tend to treat most species as though they are essentially our property. We all too often behave as though we are free to brutalize or drive them to extinction at our own discretion.” Yet, we should also recognize how we treat most human and non-human life as intellectual property.

Environmentalism should be an investigation on the rights and responsibilities of rich and poor, powerful and less powerful, old and young, men and women, humans and non-humans, the self and the other(s), individuals and collectives. While environmentalists are often intolerant of one another, diverse and disparate communities of environmentalists can also benefit from representing themselves as a coherent global movement.

Why should we emphasize the importance of diversity when discussing a homogenous label, particularly one so increasingly meaningless as ‘environmentalist’? Diversity and originality strengthen the integrity of collective identities, precisely by challenging the illusions and metaphors that make a collective identity homogenous, meaningless, and ultimately ineffective. In this sense, originality is uncomfortable because it challenges the ‘common sense’ and authority of norms that lifeless representations of collectiveness are (covertly) based on.

The armchair environmentalist (MQ Publications, 2004), book by Karen Christensen. Art by Fionna Hewitt, 2004. Source: AbeBooks

Collective originality challenges meaningless representation by offering revived and reinterpreted sensibilities that reinforce and recreate the diversity a collective thrives on. When our need for acceptance and group affiliation is lead by fear of life without it, this makes collectiveness inauthentic, confounds originality, and sends us fleeing and fiending for public space to palliate our anxiety about the collective identity.

Neil Evernden thought of this as the ‘sacred horror’ about our own curiosity and desire to be nomadic. Both Evernden and Paul Shepard agreed that the human potential for self-annihilation is based on our inauthenticity. When our social meanings and group affiliations fail to explain or justify the illusion of ‘nature’, we experience anxiety. This anxiety produces a phenomenon in which we frantically label our ecologically-centred identities as ‘environmentalism’.

Graham Saul’s study is a sluggish attempt to understand this phenomenon and its labeling. The study fails to properly explain the illusion of the ‘environment’ and the homogeneous characterization of a diverse and authentic movement that seeks to collectively explain or understand the illusions of ‘environment’ or ‘nature’. We should not assume that all environmentalists even believe in an ‘environment’, let alone any of the same things. Labeling environmentalists successfully blurs all the diversity and margins of the movement under a monolithic, artificial, and inauthentic brand.

“Lonely Tree, Lonely Planet” installation by artists Jacek Bozek, Klub Gaja, Agnieszka Gradzik, and Wiktor Szostalo. Source: Tree Hugger Project

Unfortunately, this study is the type of metaphor that masquerades as scholarship, entertains the innocence of a human-centred future, and reproduces the very anxiety that true environmentalism seeks to investigate and account for. Despite being aware of the contentious gaps and distasteful misrepresentations in their research, the Executive Director of Nature Canada has not addressed or acknowledged this in any way to date. In such a situation, especially when it comes to the sustainability and stewardship of our planet, public critique of such narrow and misinformed portrayals is essential

Remy Bargout is a policy analyst in the Food Security and Environment branch of Global Affairs Canada, and a new PhD candidate in the School of International Development and Global Studies at the University of Ottawa. The author’s opinions do not mirror the views of affiliated organizations.

Reblogged this on POLLEN.

I used to be an environmentalist, or used that word to partly describe myself, and i knew many others–ranging from academics, NGO types, to drect action ‘earth first’ types. I had some fun times with the envirionmentalists and doing actions, and also felt i was helping save the planet, but after awhile realized it was really not very fun even if i was told it was — it was more like when i was out in -45F weather which was fun for awhile but after that wasn’t.

Since i’m partly a ‘bean counter’ i also wasn’t sure about how much environmentalists are ‘saving the planet’ –in some ways they seem to be, in other ways not (especially me). I decided i am actually just part of the environment, but basically a part environmentalists either don’t save or are unaware of. (Thats why i use the nickname ‘ishi crew’ (after ishi, the’ last wild indian’ ; crew is what we call gangs around here—-my gang has 1 surviving member.)

The environment is in danger and will soon be on a verge of ending if possible measures of its prevention will not be taken up seriously. It is not only the responsibility of environmentalists but all of the citizen to prevent the earth from destruction.