By Robert Fletcher

Market-based conservation instruments’ continual “failing forward” exposes the naked emperor of an unsustainable capitalism. Post-capitalist degrowth is our only salvation.

A recent Guardian article claims that the vast majority of forest caron offset projects managed by one prominent firm, Verra, have, despite more than one billion euros of investment over more than a decade, produced no “genuine carbon reductions”. This is merely the latest in a long line of similar concerns raised about such so-called “market-based instruments” (MBIs) for biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation. In 2017, for instance, Rainforest Foundation UK asserted that despite a similar amount of investment and timeframe, World Bank support of the popular REDD+ (Reduced Emissions through avoided Deforestation and forest Degradation) mechanism had “not yet prevented a single gram of forest carbon from entering the atmosphere.” Similar examples could be multiplied endlessly.

Notwithstanding such concerns, however, almost every prominent organization in the world concerned with conservation has enthusiastically endorsed MBIs, from international financial institutions like the World Bank and Global Environment Facility to intergovernmental bodies like UNEP and UNDP to NGOs including Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund, and many others. Moreover, the recently finalized Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework intended to guide conservation efforts worldwide over the next decade continues to promote MBIs as one of its central tools.

Unveiling the Coalition for Private Investment in Conservation at the 2016 World Conservation Congress, Honolulu, Hawaii. Photo credit: IISD/ENB Diego Noguera.

Failing Forward

In my new book Failing Forward: The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Conservation, I outline and analyze this long history of MBIs’ promotion despite their significant shortcomings.

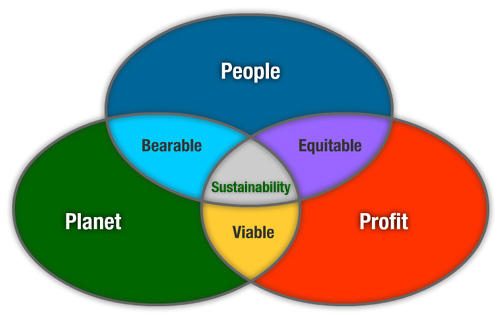

As the title suggests, I describe this as a process of “failing forward,” whereby one new MBI is rolled out after the next, each with the promise to compensate for the deficiencies of the previous and thereby achieve even bigger and better results for “people, planet and profit” simultaneously.

Supporting people, planet and profit simultaneously? The “triple bottom line”: Source: Grid Files

And when each new MBI proves to be similarly problematic as the previous, this deficiency is typically explained away with a series of predictable arguments, from the lack of “political will” to implement it properly to the fact that (notwithstanding three decades of activity) it is still only “early days” in MBIs’ development. In this way, the expectation of future success can be sustained whatever the reality of present failure.

As if to directly illustrate this analysis, after initially disputing the Guardian’s findings, Verra has since pivoted to announce that it will terminate its current offset projects to develop a new methodology to govern future projects more effectively.

Saving nature by selling It?

MBIs’ fundamental logic, consistent with the neoliberal reasoning in which they are grounded, holds that if conservation can be shown to generate more profit than the resource extraction it seeks to combat, basic economic rationality will direct investment into the former rather than the latter, and global markets will follow suit by allocating capital to conservation in an escalating virtuous cycle. Yet in practice, it has proven extremely for difficult MBIs to outcompete extractive industry in pure market terms.

While this difficulty is also consistently explained away as merely a problem of implementation (“getting the market right”), my analysis suggests that it is actually due to MBIs’ basic nature. Extractive industry, after all, generates profit by externalizing environmental and social costs, the very things MBIs try to internalize to reconcile sustainability with economic gain. As a result, the sustainability they pursue limits the revenue MBIs are able to generate. Even more damning, MBIs are usually funded precisely by offsetting extractive industry itself. Paradoxically and perversely, therefore, expansion of MBIs also requires resource extraction to expand. And if this is the case, then MBIs must inevitably fail in their aims.

Catastrophic but not serious

Why, then, do so many powerful organizations and actors continue to stake the future of our planet on neoliberal conservation instruments that are surely doomed to fail? While cynics may assert that few proponents really believes that MBIs will work – that this is really just a form of greenwashing allowing corporations to get on with business-as-usual – in my research I have encountered many really smart and successful people who appear to genuinely believe in MBIs’ potential. Many of them have, indeed, given up much more lucrative careers in other sectors to pursue something they feel is in the greater good.

To try to make sense of all of this, I turned to Lacanian psychoanalysis, which has made strong inroads into social science recently largely due to the tireless work of Slavoj Žižek. From a Lacanian perspective, proponents of neoliberal conservation mechanisms can be understood as akin to a smoker who is able to continue their addiction in the present despite its well-known harmful impacts by convincing themselves that they will indeed quit and redress the damage caused at some point in the future. In this way, as Žižek phrases it, we can continue to act as if our current situation is “catastrophic, but not serious.”

The fantasy of sustainable capitalism

At its heart, I believe, what neoliberal conservation is ultimately about is supporting the possibility of decoupling: that environmental impacts can be divorced from economic growth and hence that the latter can be sustained indefinitely. It is precisely the economic gain through so-called “non-consumptive” resource use that neoliberal MBIs promise that allows faith in decoupling to be sustained. In this way, the venerable critique asserting fundamental biophysical limits to growth can be countered and the fantasy of a sustainable global capitalism maintained.

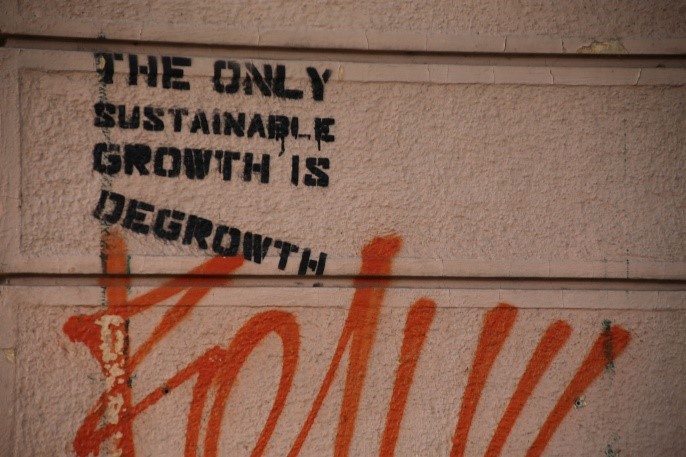

But if MBIs and other forms of fictitious capital don’t work, then widespread decoupling is impossible, capitalism is inherently unsustainable, and consequently degrowth coupled with dramatic wealth redistribution becomes the only viable way to reconcile social justice with sustainability. And given that capitalism is an economic system relying on continual growth to overcome intrinsic contradictions, genuine degrowth must necessarily be post-capitalist as well. In the realm of biodiversity governance, this entails pursuit of what elsewhere Bram Büscher and I have labelled convivial conservation.

Degrowth. Warsaw, Poland. Photo credit: Paul Sableman.

Transcending capitalism will certainly not solve all of the daunting problems confronting us. But it is a good place to begin.

Robert Fletcher is Associate Professor of Sociology of Development and Change at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. He is the author of Romancing the Wild: Cultural Dimensions of Ecotourism (Duke University Press, 2014) and Failing Forward: The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Conservation (UC Press, 2023), and co-author of The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature beyond the Anthropocene(Verso, 2020).

Top Image: Cover of Fletcher’s new book Failing Forward.

* This blog was originally published in the Political Ecology Network’s(POLLEN) blog

One Comment