By Dimitar Tsigoriyn, Paula Paraschiv, Iris Wiggerts and Sara Zimmermann

It is important to deconstruct who and what we honour and remember through the monuments and representations of history in our cities, as well as to reflect on how, and on what grounds, we bring about this remembrance.

Protesting and removing colonial statues has become one of the central political events of the past year. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement against institutionalized racism and the protests against the murder of George Floyd, a wave of monument removals and defacing has swept around Europe and the world in an effort of reconsidering the ‘glorified’ history of the age of ‘discovery’, imperialism, colonialism, and slave-trade as symbols of centuries filled with wrongs.

While in the USA, the UK and other countries several statues have been removed, in the Netherlands all statues are still standing. This does not mean that the BLM protest did not affect Dutch society. After tens of thousands of people demonstrated in June 2020 all over the country, three teenage girls fought successfully for the inclusion of racism in the national curriculum and the Prime Minister has had several meetings with BLM activists. Nevertheless, in Rotterdam, like everywhere in the Netherlands, statues have been debated, honoured, and kept in their places.

Statues as a centre of debate and symbol for power structures are not a recent phenomenon. Statues of monarchs during the French revolution, of the dictator Saddam Hussein after the US invasion of Iraq, or of colonialist Cecil Rhodes in 2015 in South Africa, were destroyed or taken down. Nevertheless, these actions always happen in a socio-political context that structure the debates and protest. And it is important to recognize these contexts as they structure conversations and narrative. Reni Eddo-Lodge demonstrates this in her analysis of the 2015 protests to have another Rhodes statue removed from England’s Oxford University. She describes how at the time, the narrative was changed from a critical reflection of colonialism and the actions of Rhodes, towards a debate concerning free speech and sensitivity, corresponding with the context of structural racism and “colour-blindness” among England’s predominantly-white population. Yet this past June, in the midst of the global BLM protests, thousands protested again in Oxford as part of the “Rhodes must fall” campaign, forcing the university to a decision about removing the statue in 2021.

In 2015, protesters in Oxford protested unsuccessfully for the removal of the Rhodes statue in Oriol College. This June, thousands took again to protest there. Source: Postcolonialist

In the Dutch context, citizens’ perceive themselves as inherently tolerant and inclusive. Consequently, as the United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights points out, racism and other injustices are not perceived as a crucial issue and thus, experiences of racism and critical reflections on colonialism are denied or unheard. Gloria Wekker, an Afro-Surinamese Dutch scholar, would call this “white innocence”. Additionally, the decades’ old debate around the traditional celebration of black facing on Saint Nicholas Day (‘Zwarte Piet’) has polarized the Dutch society: some, including the current Prime Minister, defend it as part of tradition and, thus harmless (sic), while others define it as offensive and racist.

It is thus imperative to look behind the tolerant self-image, to acknowledge different perspectives and criticism. As four students from Erasmus University Rotterdam, we decided to explore the city of our studies with open eyes, to see whether the same discourse of racial, environmental, and gender injustices still prevails through some of the city’s monuments, as we walk its streets. We analyse the background of historical figures behind street names or statues. While acknowledging the complexity of history, we seek a way of remembering from another perspective, moving away from the binary of cancelling or honouring, towards more reflection.

Witte de With

One of the most crowded streets in Rotterdam, packed with bars and restaurants, is the Witte de With street, named after Witte Corneliszoon de With, an important Dutch naval officer in the 17th Century. Nowadays, most young people have a positive association with the name ‘de With’ as they imagine drinks, party, and affordable Arab food. Witte de With’s life and actions seem to be fading into the background. And if there is something worth remembering, then it is his contribution to the Dutch ‘golden age’. This, however, denies the complexity of his actions, but more importantly, of the times he was living in.

Witte de With street. Photo by Paula Paraschiv

De Witte worked for both Dutch trading organisations, first the Dutch East India Company (VOC), then the Dutch West India Company (WIC). Both companies represented the Dutch interest in trade, war, and colonization outside of Europe. As a teenager, he joined the VOC as a cabin boy and participated in the key conquest of Jakarta (nowadays Indonesia) in 1619. Jakarta, renamed Batavia, became the local headquarters of the VOC, from which the Dutch expanded their influence through colonial violence, as for example with the genocide on the population of Banda (nowadays Indonesia) in 1621. De With, as captain, took part in battles on the Moluccas (an archipelago in nowadays Indonesia) in 1625, where he also destroyed around 90.000 clove trees. This practice was used to drive the price of the valuable spice up and to protect the Dutch monopoly. Once one looks at this through the lens of Political Ecology, it seems clear that the destruction of clove trees was a display of De Witte’s hierarchical relation to the land that he destroyed, as well as to the locals who lived there. Apparently, that nature was seen primarily as a resource for exploitation and profit. This hierarchical thinking was the necessary foundation to justify the cruelties and injustices both against nature and ‘the Others’. However, this did not happen in a vacuum, but in a European competition towards power, wealth and hegemony over the control of colonies and trade routes.

In contrast to the street’s name which remains, the ‘Witte de With Art Institute’, situated in the same street, recently announced that it will be renamed “Melly” in January 2021. After public pressure from the Black Lives Matter movements and debates, the institute decided that it does not want to be associated with “a history of terror”.

Piet Hein

A statue that was defaced earlier in June by BLM protestors is that of the Piet Hein, a native of Delfshaven (a district of Rotterdam). A famous admiral and privateer for the Dutch Republic in the early 17th century, known for capturing a huge share of the Spanish treasure.

Piet Hein statue. Photo by Paula Paraschiv

Hein is officially known as an opposer of slavery, having been a slave himself under the Spanish Empire. Even though Piet Hein personally seems to not have been involved in the slave-trade, it is important to consider the broader context. During his time, the Mediterranean countries were involved in slave-trade and the Netherlands, fighting for independence from the Spanish, officially opposed it. However, records show that during this war, the Dutch captured Spanish ships with slaves, and since they were not able to sell them in the Netherlands, they were taken to Antwerp, or sold directly to the British.

Moreover, with the gold captured by Hein, the Dutch West India Company (WIC) launched a large-scale attack on nowadays Brazil that resulted in the instalment of a governor sustaining the sugar industry and slavery, starting a new era for the Dutch colonial activities. Understanding the profit opportunities from the trade in slaves and agricultural products, the WIC started in 1637 official slave-trade operations. Even though the Dutch WIC became officially involved in slave-trade only 7 years after Hein’s death, the plans were made during his lifetime and the topic was part of the public discourse, with opponents and supporters. For instance, in 1617 the WIC fortified an island, called Senegambia (part of nowadays Senegal), mainly for slave-trade purposes.

Historical sources about these times are scarce and if there are documents, they are mainly produced by European powers. Thus, making claims about Hein’s involvement in slavery, either celebrating him as an anti-slavery hero or as a slave-trade profiteer, is somewhat speculative. Nevertheless, the broader picture clearly shows the involvement of the WIC –for which Hein commanded several missions– in the slave-trade and the problematic way of ‘making business’ during those times.

Pim Fortuyn

Even though colonialism is often perceived as a thing of the past, its ideologies persist until today. Not only are there still statues of the colonial, white male heroes, but new statues are being built. The statue of Pim Fortuyn, created in 2003, in the Centre of Rotterdam is a good example. Fortuyn was a Dutch far-right populist politician in the early 2000s, prominent for his anti-immigration xenophobic stances and assassinated in 2002, just before the national elections. Recently, the statue was spray-painted by BLM activists, cleaned, and then honoured by local right-wing groups. These groups followed the national example of Thierry Baudet (from the right-wing party “Forum Voor Democratie“), who toured the Netherlands to honour colonial statues, such as those of Piet Hein and Jan Pieterszoon Coen, another VOC admiral in the 17th Century.

Pim Fortuyn statue. Photo by Paula Paraschiv

These statues are not accidentally in the middle of this conflict. They are not just symbols of the past, but the foundation of the racist colonialist discourse that still lives today. Fortuyn argued during his lifetime against religious freedom, about the ‘backwardness’ of Islam, and for the moral superiority of Christians within his country. The roots of this argumentation, however, are not recent. It is the colonial idea of Western superiority, of the ‘primitive other’ and the ‘civilized we’, which serves as a moral justification for actions, both then and now. The simple dualisms deny the existence of complexities and historical injustices. This makes it easy for current leaders and politicians to idolise not only colonial statues but also colonial discourse and ideas.

Paradoxically, it is not the right-wing minority, like Baudet and his followers, but the self-described tolerant majority, that ensures the status quo and its colonial legacy to continue. Wekker describes how the ‘white innocence’ of the Dutch population leads to an exclusion of other narratives, leading to the failure of critically reflecting on the colonial times, but also of acting upon current injustices, which are in many ways rooted in that colonialism. There is also a failure of reflecting on the context of the statues and street names themselves. Instead, statues continue to be built, streets and institutions wear the names of the ‘heroes’ of those colonial times, and schools teach students about the ‘golden age’ of the Dutch empire. Both, the Witte de With street and the statue of Piet Hein, were not created within their lifetimes, or shortly after their death, but more than two centuries later, at the height of the European colonial powers. The statue of Hein was made in 1870 and the street was named after de With in 1871. So, it is high time, to have a look behind the curtain of ‘white innocence’ and ask again, who is being remembered, how, and why.

Imagining an alternative

How can we make sure to still think about and embrace history, while at the same time critically reflect upon it? The historical monuments showcasing or bearing the names of white male figures that have exploited natural and human ‘resources’ in their pursuit of profit and glory, are not doing justice to the other, ‘silent’ stories.. The current indifference towards colonialism and our memories of our history lead to a blindness of past and current injustices. For our society to indeed showcase changed rhetoric, we should perhaps re-examine the monuments that are standing tall on the streets of our cities. As philosopher and trans activist Paul Preciado argues: “When a statue falls, it opens a possible space of resignification in power’s dense and saturated landscape.” He suggests to “use the empty pedestals left behind in all cities as performative platforms that other, living bodies can stand atop.”

Reimagining the Piet Hein statue. Pictures by Paula Paraschiv

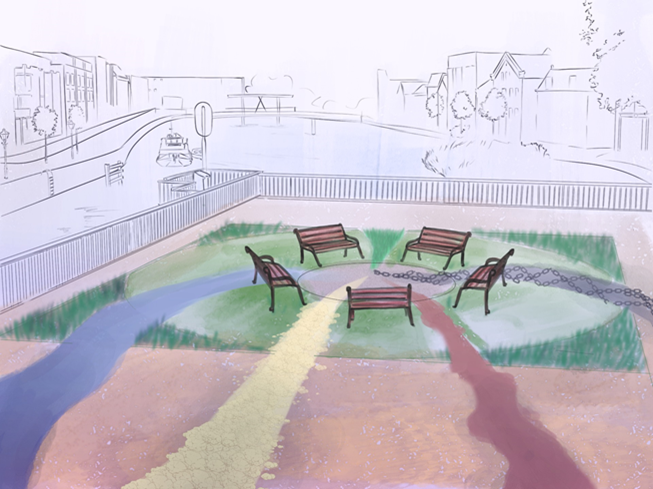

With these ideas in mind, we took the liberty of ‘redesigning’ the monument of Piet Hein, by taking into account both his contributions to the Dutch society, as well as the different controversies surrounding his actions. Instead of a monument with his figure, we deemed it more pertinent to position a garden, and in its middle, five benches facing one another, a place of conversation and reflection. Thus, instead of maintaining the hierarchical relations (the idea of looking up to a stone statue representing a white man whose success was built exactly on this hierarchical discourse), there would be a possibility for reciprocity, exchange and complexity.

More symbolically, around the benches we envision five ‘paths’, each telling a different story related to Piet Hein’s actions and the times of his activities. Thus, replacing the statue does not ‘erase history’, as claimed by many right-wing politicians, but it means acknowledging the importance of more than one narrative. In our example, five stories are told, which does not mean that this is a finite number, only an idea illustrating the complexity of Hein’s life and the context of his actions. The following are the narratives that we thought of, which can be integrated into the garden in the form of infographics, quotes and texts.

Reimagining the Piet Hein statue. Artwork by Lina Grecu

The golden path is probably the most known part of history. It tells the story of Hein’s contribution in the form of gold to the Dutch economy, but also the political independence. The blue path tells the story of the Dutch (West and East) India Companies, their business strategies and sea routes, Hein’s involvement, and the geopolitical implications across the world. The green path tells the story from the point of view of the environment. It talks about the plantations, forest destruction, and the introduction of foreign plants to other parts of the world. It problematizes the exploitative idea of colonialism and the effects of this, felt even today. The next path, made from iron chains, represents the painful history of slavery and the Dutch involvement in it. Lastly, there is a red path, referring to the blood that was shed in the colonial expansion –in the war with Spain, and in the millions of indigenous peoples who lost their lives in slavery or defending their territories.

With this said, it does matter not only who and what we honour and remember through the monuments and representations of history in our cities, but also how and on what grounds we bring about this remembrance.

—

Dimitar Tsigoriyn is a 3rd-year Bachelor student of International Business Administration.

Iris Wiggerts is doing an International Bachelor in Economics and Business Economics.

Paula Paraschiv and Sara Zimmermann are doing their Bachelor in Management of International Social Challenges.

This post was begun by the authors as the final essay of the interdisciplinary Erasmus University Honours Course on “Feminist Political Ecology”, taught by Prof. Wendy Harcourt.