By Kat Taylor, Sheri Longboat and Quentin Grafton

Water governance frameworks need to harmonise with United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Editors’ Note: This post is the first in the series “Reimagining, remembering, and reclaiming water: From extractivism to commoning”, which looks at struggles over more just and ecological water presents and futures. The series is co-organized by the Undisciplined Environments and FLOWs blogs.

_

Water justice for Indigenous peoples is long overdue. Too often, dominant water governance frameworks reproduce water colonialism, ignoring Indigenous peoples’ water rights, responsibilities, and governance systems. International guidelines, such as the OECD 12 Principles on Water Governance (hereafter the ‘OECD Principles’), could do more to redress this issue.

Water rights, water responsibilities

‘Water colonialism’ is the worldview, or policy, based on colonial imperialism that underpins the colonisation of water. Water colonialism normalises settler occupation of land, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples of water, and legitimises settler exploitation of water. Many Indigenous people do not see land, water and people as separate. However, a land/water separation is often imposed by settler states’ property rights regimes. This can result in a settler state recognising rights to land but not water (see this example from a Barkandji man, William ‘Badger’ Bates). Thus, it is helpful to consider how colonialism manifests and impacts in relation to water specifically.

If we assume that water colonialism is indeed a problem- what to do about it? There is no ‘one size fits all’ solution. One benchmark that helps us to understand and frame the issues at stake is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). UNDRIP defines and protects rights of Indigenous peoples not covered by other international charters; specifically, political, cultural and territorial water and water related rights.

UNDRIP now plays an increasing role in shaping legislation in different countries. For instance, British Columbia, Canada, passed legislation to become the first province in Canada to “implement” UNDRIP. Yet we must consider responsibilities and relationship to water, not just rights. Systems of Indigenous law and knowledge emphasise that water justice must involve caring for and protecting water (i.e. responsibility), and making water decisions in accordance with Indigenous values. For example, the siwɬkʷ Water Declaration states: “When we take care of the land and water, the land and water takes care of us. This is our law”. Along these lines, the Indigenous Peoples’ Kyoto Water Declaration states “Our traditional knowledge, laws, and ways of life teach us to be responsible in caring for this sacred gift that connects all life”. Inherent responsibilities (and rights) are embedded in knowledge systems and codified in Indigenous law which exists since time immemorial. Thus, whilst some rights are recognised by UNDRIP, the primary source of Indigenous peoples’ responsibilities (and rights) to water are their own systems of law.

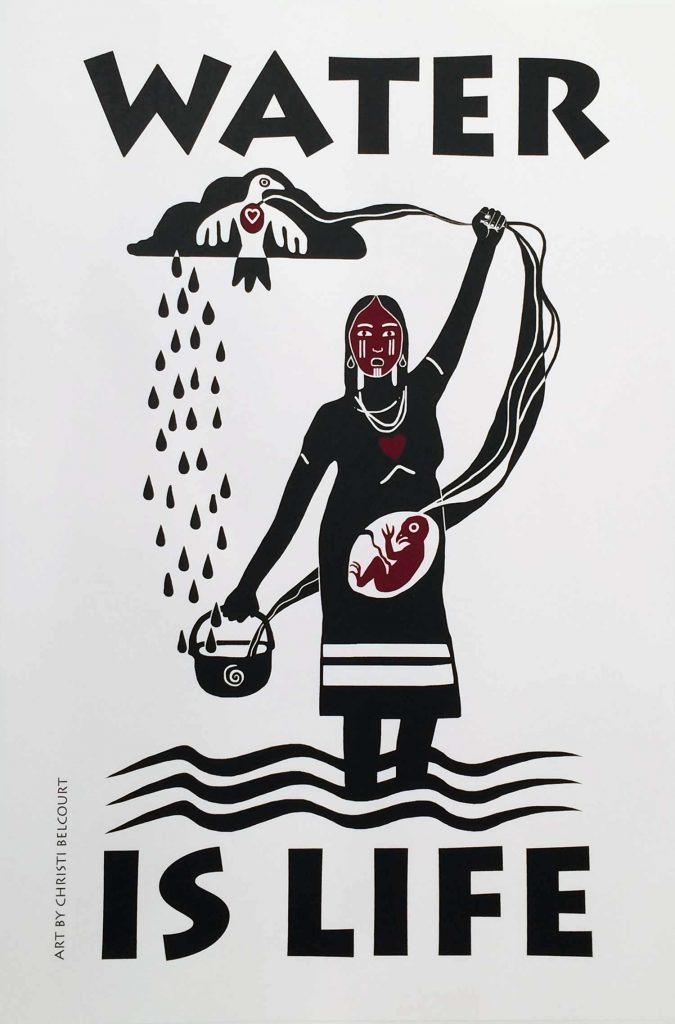

Poster by indigenous Michif visual artist Christi Belcourt from the Onaman Collective, a community-based social arts and justice organization helping indigenous youth to reclaim the richness of their culture. Source: Onaman Collective.

Water governance frameworks should harmonise with UNDRIP

UNDRIP has significant implications for the way water is distributed, managed, used and governed. One of the Declaration’s Principles is that Indigenous peoples have the right to use, own and control waters within traditional territories (article 26). This includes inherent rights to their own political and cultural institutions (article 5) i.e. laws around water. The right to self-determination (article 3) and decision making in matters that may affect their rights (article 18) can also be applied to water. In many jurisdictions, this would mean a redistribution of water access, power and authority, and fundamental changes to governance.

Centering on Indigenous peoples’ water governance has wide benefits

Right now, there are exciting moves towards Indigenous law and legal pluralism for water. For example, the Cowichen Watershed Board, Canada, the Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council, and the Iwi/Crown shared guardianship of the Whanganui River in Aotearoa/New Zealand. There is revival and reclaiming of transboundary governance through coalitions like the Coast Salish Aboriginal Council, Canada or the Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations confederation, Australia.

On a pragmatic level, settler states would be wise to consider UNDRIP obligations within water governance frameworks. This promotes consistency. In the long term, UNDRIP implementation can reduce conflict, increase certainty for all water users, and ensure water’s benefits are shared equitably.

As water ethics becomes increasingly important, settlers have much to gain by appreciating Indigenous peoples’ perspectives that have been generously shared. One example is the application of the Great Lakes Anishinaabe First Nation’s Seven Grandfathers as Water Governance Principles. The Seven Grandfathers are Truth, Humility, Respect, Wisdom, Honesty, Love and Bravery. These teachings form a moral code. After interviews with Anishinaabe Elders, Longboat suggested an interpretation of the Grandfathers as water governance Principles:

- Truth–Value water in all its forms and all its uses

- Humility–Equity of all people, equity of nature, nature’s rights to water

- Respect–Respect water and all of nature, and one another’s views and ways

- Wisdom–Use water wisely and consider all forms of knowledge

- Honesty–Accountability and transparency of actions, decision-making and motives

- Love–Commitment to collaboration and shared benefits

- Bravery–Address immediate problems and address new conflicts from resistance to change

The Seven Grandfathers as Water Governance Principles is but one specific example. Of course, water governance principles must fit the context. Indigenous peoples’ cultural and intellectual property needs to be respected too. What we are trying to illustrate is that possibilities exist for redefining hegemonic water governance norms based on Indigenous knowledge and ethical principles.

Integrating Indigenous rights in the OECD 12 Principles on Water Governance

The OECD Principles are voluntary guidelines for water governance. Established in 2015 by the OECD’s Water Governance Initiative, they have been adopted by 42 countries globally. The OECD Principles are grouped into three dimensions: effectiveness, efficiency and trust and engagement. In Table 1 we list the Principles. More details about the OECD Principles and their implementation are available from the Water Governance Initiative.

Table 1. The 3 dimensions of the OECD 12 Principles on Water Governance.

| Dimension | Principle # | Principle |

| Effectiveness | Principle 1 | Clear roles and responsibilities |

| Principle 2 | Appropriate scales within basin systems | |

| Principle 3 | Policy coherence | |

| Principle 4 | Capacity | |

| Efficiency | Principle 5 | Data and information |

| Principle 6 | Financing | |

| Principle 7 | Regulatory frameworks | |

| Principle 8 | Innovative governance | |

| Trust & engagement | Principle 9 | Integrity and transparency |

| Principle 10 | Stakeholder engagement | |

| Principle 11 | Trade-offs across users, rural and urban areas, and generations | |

| Principle 12 | Monitoring and evaluation |

Source: OECD, 2015.

How do the OECD Principles support Indigenous peoples and their water rights/ responsibilities? To find out, we did an analysis of OECD documents related to the 12 Principles. We explored what assumptions were made about water decision making, settler states and Indigenous peoples.

Overall, the OECD Principles reflect the dominant settler-colonial perspective of water. Implicitly, the OECD Principles are aimed at settler-state governments, assuming a single water governance authority. Throughout the text, Indigenous peoples framed as ‘under-represented groups’, and sometimes ‘stakeholders’ rather than self-determining peoples with own water governance, laws & institutions. There is a sentence about ‘Recognition of the customary access and rights to water’ and a case study about ‘engaging Indigenous communities’ in the companion document on Stakeholder Engagement. However, Indigenous peoples’ rights are not well integrated into the overall framework.

Water is presented as a ‘resource’ to manage, not as something that might have a spirit or be an ancestor. UNDRIP was not mentioned within the documents (nor, for that matter, Indigenous peoples’ water responsibilities). It could be argued that it is not necessary to list every international agreement, declaration and standard. But how can water colonialism be addressed without explicit attention to Indigenous peoples’ rights?

We provided this critique not to single out the OECD Principles in particular. Rather, the intent is to show that colonialism is replicated in water governance frameworks—even ones that are otherwise very robust. Water justice cannot be achieved as long as Indigenous peoples’ rights, responsibilities and their governance systems are made ‘invisible’ whilst settler frameworks of ‘resource management’ are the default.

The pathway ahead

We came up with some initial ideas for enhancing the OECD Principles. These included: reviewing and revising the framework, adding a new ‘water justice’ dimension to the current Principles, or developing a companion document that explicitly considers UNDRIP obligations. Change, if it occurs, needs to be led by Indigenous people. For example, a water experts’ group of Indigenous peoples could be invited to advise Water Governance Initiative on how the OECD Principles might be enhanced to address water colonialism, support Indigenous peoples’ rights, or whatever is deemed an appropriate strategy.

International standards face the inherent challenge of trying to create universal frameworks for a complex world. At the local level, water governance must fit the context. Settler states need to work together with Indigenous peoples, leader-to-leader, nation-to-nation, to develop a way forward. International frameworks establish norms; at the local level they may feel irrelevant, and yet the impact on shaping the global water discourse cannot be dismissed.

There is still a long way to go. Models branded as Indigenous-settler ‘co-governance’ don’t always share power equally. Co-option and tokenism are a real risk. But change is happening. Harmonising water governance frameworks with the human rights standard of UNDRIP is an important step towards water justice.

—

Kat Taylor is a PhD graduand at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy, Australia, and the Managing Editor of the Global Water Forum. Prior to her PhD studies she worked on community-based water and environmental health projects.

Sheri Longboat is an Associate Professor at the University of Guelph’s School of Environmental Design and Rural Development, Canada. She is a Haudenosaunee Mohawk and band member of the Six Nations of the Grand River with twenty years of experience working with Indigenous communities in Canada.

Quentin Grafton is Professor of Economics and UNESCO Chair in Water Economics and Transboundary Water Governance at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy. He is an Australian Laureate Fellow (2020-2025), a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, and both a former President (2017-18) and Distinguished Fellow of the Australasian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society (AARES).

Note: This blogpost is based on the original article in the journal of Water (2019)

Top (feature) image: Majala (Barringtonia acutangula) is a medicine plant on Nyikina floodplains, Kimberley, Western Australia. Source: Kat Taylor.

5 Comments