by Elena Louisa

The promotion of food (in)security over decades has achieved to govern the way we think about alternatives to industrialised agriculture. Global famine is not a problem of food scarcity but a legacy of unequal power structures which are weaved into past and present agri-food systems. Agriculture based on permaculture can embrace localized food supply and be part of context-specific solutions to today’s food challenges.

Source: https://transitionnetwork.org

First listen, then read:

I remember when I first heard of Permaculture. It was not in a seminar in university about sustainable agriculture, nor in one of these gardening projects which popped up in every little unused corner of my home town Berlin. It was at a concert of the Australian band ‘Formidable Vegetable Sound System’ on one of these rare summer nights in Hamburg, where you can stay outside until the middle of the night without getting goosebumps. Four bearded, hippish looking men on the scene singing:

… if your food only had one flavour

If anything that you said was right

it wouldn’t work to you favour

Variety is the spice of life …

What followed was a child-like curiosity, when you discover a new world you weren’t even aware existed. It was the start of an adventure, on which I spent summers working on organic farms, started urban agricultural projects and attended conferences on alternative food systems. I was submerged into a cascade of inspiration, and I experienced a sense of community and empowerment through collective work backed by a global network of permaculture activists, scholars and practitioners.

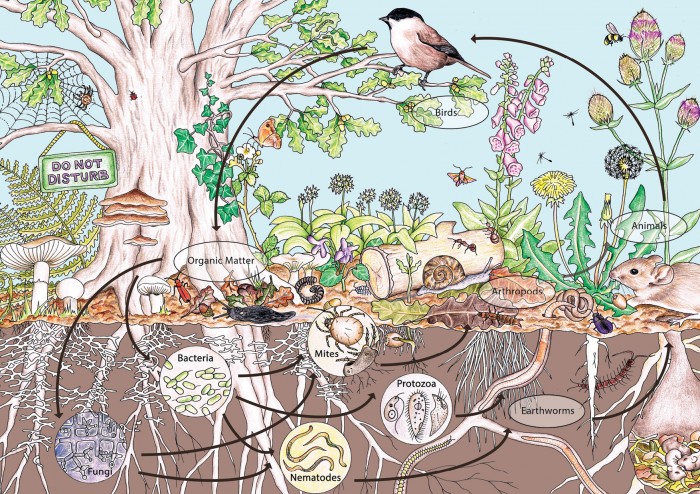

It was the simplicity of the permaculture principles and its way of approaching the social and natural system as something interconnected, by which I was fascinated. Namely, designing landscapes, which mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature and produce food, fibre and energy for provision of local needs. By doing so, permaculture contributes to small local changes that are directly and indirectly influencing actions in fields like sustainable development, organic agriculture, appropriate technology and intentional community design (Holmgren 2013).

features of permaculture. Source: https://www.frogtownfarm.org

But whenever I left the safe space of my little eco-bubble, I was confronted with critiques of people who told me that what I was doing was not enough to feed the world. That a few permaculture farmers could not eradicate famine, and there was no way permaculture could cope with the pressure that the inevitable population rise will bring on the food system. I was told that we don’t have time for the “slow” gains of an agricultural system based on permaculture and that prevailing food insecurity forces us to find faster solutions now (see the critical analysis of Fraňková et al. 2016; Alcock 2009, and Jarosz 2011, regarding the root causes of the food insecurity narrative).

Hearing this always knocked the wind right out of me. Such arguments leave you wordless. Maybe it’s because they make you realise the privilege you hold of coming from a country where your grandmother’s generation was the last one that really suffered from hunger. Or because you don’t quite have hard data at hand on how many people can actually be fed by small-scale agriculture (see the article by the International Institute for Environment and Development on this issue).

And then, there was this appalling statistic that cast a shadow over everything I was fighting for. How could I stick to my local engagement, when there were still 805 million people who were chronically undernourished in 2014 according to estimations of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO, IFAD & WFP 2014).

Statistics make for powerful arguments. They even melt away my aversion to ‘big-ag’ when I see a picture of what a future food landscape could look like. The photograph of Luca Locatelli, named “Hunger Solutions”, won the second prize of the Word Press Photo awards in 2018, and is one such picture. Industrial farmland surrounded by experimental parcels touching the very horizon of a little piece of the earth somewhere in the Netherlands. Suddenly such a scenario appears to be persuasive when we think of combating hunger.

And then, there is also the old Malthusian argument, as if raised from the dead (if it ever died) to remind us that actions are urgent. This simplified formula that an increase in population will inevitably lead to a lack of food and to misery for all humanity, and that therefore we must act immediately to avoid the worst (see this book chapter about Malthusian theory).

The unruly activism to secure food and the desire to help those lacking food provision, however, can blur our understanding of the root causes of hunger or undernourishment for some and affluence for others, although there is indeed enough food produced for everyone to eat (Eric Holt-Giménez 2018, and the interview with Eric Holt-Giménez). Examining and listing the reasons why this imbalance exists could go on forever. For me, it starts with land dispossession in the Global South.

Throughout and after the official colonialist era, when plantation economies were being established for capital accumulation, the local people were made bereft of their very means of subsistence (Nally 2011). Costa Rica is exemplary for such development, where banana enclaves were established in the Caribbean region of the country in the end of the 19th century and most of the land was owned by the foreign United Fruit Company (today Chiquita). Local people not only became dependent on the employment by the company but their whole life – communication, commerce, mobility – was determined and controlled by the plantation owners (Wagner 2012). Today, we see much of this land being converted to produce fuel crops; biomass that serves mostly the fuel demands of the Global North, instead of being used to feed the local communities (see the report of World Rainforest Movement 2016).

However incomplete this list might be, it shows that uneven power structures are weaved into the past and present agro-food system. It goes some way in explaining the inequalities engrained in our global food system and how abundance and scarcity can co-exist. It clearly demonstrates a notion of what Michel Foucault describes as the biopolitics of “make live” and “let die”. A concept explaining a political rationality which takes the administration of life and populations as its subject, in order to enhance livelihood conditions (and to ‘make live’) for some while “let die” of others. The food (in)security narrative was nourished by a rhetoric of improvement of agricultural productivity with the aim to promote agrarian capitalism especially in Global South countries. However, the integration in global agrarian markets rather increases the dependencies of Global South populations and their vulnerability in situations of economic and environmental crisis in which they are often literally left to die (Nally 2011).

Notwithstanding, the food (in)security narrative is so powerful, that even the phrase “WE have to feed THEM” becomes normalized and the inherent reproduction of racism and unequal power structures are portrayed as being for the greater “good” of the undernourished.

Nevertheless, such phrase certainly depicts a process of what Edward Said and other post-colonial theorist call ‘othering’. A process in which ‘the others’, ‘the subaltern’ without agency, are placed somewhere outside a discourse, while the power of a few truth-holders is emphasized. So, it is the Dutch Scientist or a World Bank employee who presides over the agency of the entire peasantry.

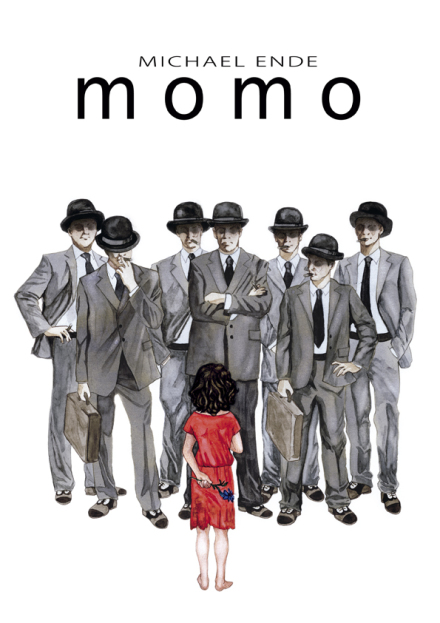

They suddenly appear and provide the world solutions to problems they created in the first place, just like the Men in Grey do (see the summary of the novel ‘Momo’). Those narrow-minded individuals of Michel Ende’s famous novel “Momo”, who are stealing humans their time. Those who are preaching efficiency and progress and are making us think that technology and the perfect allocation of means, of money, of time or even of water and nutrients to grow plants will be the solution to the major challenges humanity is facing today.

Source: https://bearskin.org/2016/07/17/momo/

Such narratives make us forget what environmental history has taught us. Namely, that every innovation throughout human history was accompanied by unforeseen side effects. That every new solution increased the complexity of society and created new problems which were solved by new innovations, which created new problems… and finally paved the way for what environmental historians call a risk spiral (Winniwarter 2010; Haberl et al. 2010). Nevertheless, Men in Grey push their agenda of technology-based solutions and progress.

And while I hear Formidable Vegetables chanting:

Cos there’s many, many,

Many, many different kinds and

many, many, many, many different places.

Many, many, many, many different times

many, many, many, many different faces

many, many, different varieties

many, many, people in society

many different opinions

on the way to do things …

I feel like someone has refused me my agency, and the one of all these many people in society who believe that a local, just and regenerative agri-food system is possible.

The Men in Grey are able to push their narrative of food (in)security not because it is true, but because they are powerful story-tellers. They’ve succeeded in governing the mentality of the people, and how they evaluate alternative ways to feed the world. As a result, they achieved dominating the discourse of how to address the problem of famine and let us think that there might be a one-size-fits-all solution somewhere over the

r a i n b o w .

But instead of quoting the dreamy lines of another band, we should rather think about addressing global hunger by dismantling the legal, institutional and biotechnical mechanisms such as trade tariffs, agricultural subsidies or intellectual property rights behind the food (in)security narrative.

Source: https://greenglobaltravel.com/permaculture-gardening-techniques/

Imagine if we worked on addressing the root causes of hunger, instead of going down the risk spiral? When we do so, when we understand hunger through the lens of biopolitics or other lenses provided by post-colonial theory, we might understand that there will never be one solution for such a complex world. But that there are a thousand alternative practices already in place and people embracing them in their very contexts.

And that they might be part of the solution to famine, challenging the food (in)security narrative to sing a different song…

Cos

… The more functioning connections

The better

You never know what it will become

Mix it up but keep it together

Let your differences work as one.

Elena Louisa Alter holds a Bachelor degree in Environmental and Political Science and is currently doing her Master in Social Ecology at the Institute of Social Ecology in Vienna. Besides studying, she is engaged in educational work carrying out seminars related to climate justice, gender justice and alternative economic practices. She also enjoys writing poems on her own blog and guest articles for a German feminist online magazine.

This is part of a series of four blog posts written by master students of the political ecology course, part of the UAB-ICTA’s Master’s Degree in Interdisciplinary Studies in Environmental, Economic and Social Sustainability. The essays were inspired by prize winning photos of the World Press Photography Awards 2018.

References:

Alcock, Rupert. 2009. Speaking Food: A Discourse Analytic Study of Food Security. http://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/spais/migrated/documents/alcock0709.pdf (last access: 05.03.2019)

Eric Holt-Giménez. 2018. Can we feed the world without destroying it. Polity Press. Cambridge.

FAO, IFAD & WFP. 2014. The State of food insecurity in the world. Strengthening the enabling environment for food security and nutrition. Rome: FAO. Available: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4030e.pdf (last access: 05.03.2019)

Fraňková, E., Haas, W., Singh, S.J. (Eds.). 2017. Socio-metabolic perspectives on sustainability of local food systems: new insights for science, policy and practice, Human-environment interactions. Springer, Cham.

Haberl, Helmut; Fischer-Kowalski, Marina; Krausmann, Fridolin; Martinez-Alier, Joan Winiwarter, Verena. 2010. A sociometabolic transition towards sustainability? Challenges for another Great Transformation. Sustainable Development. Available: here (last access: 05.03.2019)

Holmgren, David. 2013. Essence of Permaculture. A summary of permaculture concepts taken from “Permaculture Principles and Pathways beyond Sustainability. Available: https://files.holmgren.com.au/downloads/Essence_of_Pc_EN.pdf (last access: 05.03.2019)

Jarosz, Lucy. 2011. Defining World Hunger. Scale and Neoliberal Ideology in International Food Security. In: Culture & Society. Vol. 14/1. pp. 117-139.

Nally, David. 2011. The biopolitics of food provisioning. In: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. New Series. Vol. 36/1. pp. 37-53.

Wagner, Jordyn. 2012.The Effect of the United Fruit Company and the Resulting Banana Enclave on the Racial Problems in Costa Rica in the Early 20th Century. Available: here (last access: 05.03.2019)

Winniwarter, Verena. 2010. The Art Of Making The Earth Fruitful: Medieval And Early Modern Improvements Of Soil Fertility. In: Ecologies and Economies in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004180079.i-227.21

Hello – thanks – what a great contribution to this blog. Just for a bit fun – here is link to a video of The Formidable Vegetable Sound System at Glastonbury Festival 2014 – doing one of their ‘permaculture songs’. I think it’s really important that pop/folk music fully engages with environmental issues in ways which are not turgid or sanctimonious. This band certainly do that very well https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OewDXecTPIo