By J. Sebastian Reyes Bejarano, Gustavo García López, and Diego Andreucci, in conversation with Tatiana Roa Avendaño, Teresa Borasino, Marina Weinberg and Daniel Chavez

In an event last June, activists and scholars critically analyzed dominant energy transition discourses as new business horizon, as green utopia and as myth. They contrasted these with alternative visions and strategies for energy sovereignty emerging from grassroots struggles in the global south.

Last June, a roundtable discussion on “Energy Transitions from below: from climate colonialism to energy sovereignty” took place at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in the Hague. In it, five scholars, activists, and artists reflected on the consequences of hegemonic energy transition models on historically oppressed populations, as well as the strategies and opportunities to overcome colonial capitalism in the setting of the climate crisis.

The panel was formed by Tatiana Roa Avendaño, an environmental activist, educator and researcher at CENSAT Agua Viva Colombia, and a PhD candidate at CEDLA–University of Amsterdam; Teresa Borasino, a Visual artist co-founder of Fossil Free Culture NL, a collective that works at the intersection of art and climate activism; Marina Weinberg, a Senior Researcher in the Worlds of Lithium ERC Starting Grant and Assistant Professor at the Instituto de Arqueología y Museo – San Pedro de Atacama (Chile), working on the material, social and symbolic dynamics produced by lithium and copper extractivisms in the Atacama Desert; and Daniel Chávez, fellow and Senior Project Officer at the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam, focused on energy alternatives in the Global South.

The event’s moderator, Gustavo García López, introduced the roundtable with a reflection on how, in the current climate crisis, the discourse around “transition” has progresively been co-opted to become a green capitalist buzzword. Under the guise of transition towards a more sustainable economy, extractivist, colonial, racist and socio-environmentally destructive projects are being carried out to enable new capitalist fixes amid the climate crisis. These projects are largely affecting indigenous and other marginalized rural communities, while primarily benefiting elite consumption and “decarbonisation” in the global North and other industrial “cores”. Growing evidence shows that large-scale ventures on biofuel monoculture plantations, forest conservation, mineral extraction for building batteries and other technologies are promoted as substitutes for fossil fuels, merely add capacity to an ever-expanding energy regime controlled by the same large corporate oligopolies. This has led critical observers to consider such plans as primarily concerned with preserving white and capitalist class privilege in the face of climate-induced disruption, rather than “saving the planet”.

At the same time, at the frontlines of the new extractive frontiers, indigenous, peasant, black and brown people as well as radical grassroots organizations, and transformative social and climate justice movements, occupy and re-signify the discursive-political space of “transitions”. At the heart of the struggles of these populations are proposals for a truly anti-capitalist and anti-colonial transition. Questions arise about who leads, who benefits and who suffers from current energy transition trends, and what kind of radical, just, liberating, decolonising and intersectional transformation can emerge from grassroots struggles amid the ecological crisis.

Participants of the roundtable, from left to right: Gustavo García López, Daniel Chávez, Marina Weinberg, Teresa Borasino, and Tatiana Roa Avendaño

To address these issues, panellists were asked to discuss the critiques to dominant energy transition discourses and plans, as well as the alternative visions and strategies for energy sovereignty emerging from grassroots struggles.

The energy transition as global spectacle: Transition as business horizon, green utopia and myth

During the first round of interventions, a central idea was suggested by the panellists: the “energy transition” is presented as a spectacle by dominant discourses on climate policies. Reports from international organizations and institutions, and recommendations for policymakers and governments, echo throughout the world claiming the necessity of moving from fossil fuels to “renewable” energy sources to face climate change. The transition has been presented as a priority for countries in the European Community, the United States and China, and it is discursively imposed as a global concern. Concepts such as innovation, green markets, new technologies and renewable energies are part of the technocratic set of solutions to the crisis that companies are called to lead and apply.

By approaching the energy transition as a global spectacle sustained through discourses and imaginaries of what the transition should be, three analytical categories were proposed: Energy transition as a new business horizon, as a green utopia and as a myth. The category “energy transition as a business horizon”, proposed by Tatiana Roa Avendaño, indicates that the dominant discourses and plans for the transition do not question the model of accumulation and the energy matrix on which today’s Western society is based. Therefore, energy transition opens a new frontier of extraction and accumulation through which capital can be expanded by the development of new businesses. This implies that international corporations must secure the materials needed for the transition by investing in large-scale projects in sectors such as mining, agrofuels, non-conventional renewable energies or the so-called green economy.

These types of large-scale projects have been contested, primarily in the Global South, as they cause land and water grabbing, and do not solve local communities’ problems of energy access. Cases such as the wind farms in Oaxaca – Mexico, or the renewable energy projects in La Guajira – Colombia, exemplify the impacts and conflicts caused by these projects. The expansion over the new business horizons is legitimized by making invisible these impacts on local communities, ecosystems, and territories, as suggested by Teresa Borasino.

Legitimation through invisibilisation is also observable in the category “energy transition as green utopia”, proposed by Marina Weinberg. This category focuses on the imaginaries and hegemonic discourses around the past, the present and the future in the dominant plans for transition. Weinberg criticized the univocal and linear understanding of history in such plans, in which the spectacle around decarbonization promises the dream of the “earthly Eden of climate neutrality”. The notion of a plan itself, which infers the existence of a known future, does not recognize that there will be no future for millions of people suffering the direct consequences of both climate change and ecosystem degradation from the new waves of (green) extractivism.

A private property for lithium extraction in the Atacama desert. Source: Photo by Marina Weinberg.

In these dominant transition plans, the “green utopia” will be achieved in those countries where industrial power and technology are concentrated. Consequently, the whole world becomes the larder from which resources are drawn to make the technological chimaera possible. While technological fixes and uninterrupted economic growth in the global north are seen as essential to achieving the green utopia, the regions from which the resources for transition are extracted suffer increasing inequality, dispossession, and the destruction of life-supporting ecosystems. These regions of extraction are seen as “laboratories” in the early stage of the transition, as in the case of desert ecologies of northern Chile, where the physical characteristics of space, such as abundant solar radiation, make it a target for evaluating the development of new energy enterprises, including lithium mining.

Finally, the category “energy transition as myth”, proposed by Daniel Chávez, allows an understanding of how spectacular discourses by international organizations – stating with optimism that the energy transition is being achieved or that it has already started and merely needs to go faster – become a tool that demobilizes the criticism and actions of academics and environmental activists, who push for a meaningful and socially just energy transition. A recent report published by TNI with Trade Unions for Energy Democracy argues that there is no real energy transition, but rather an energy expansion: renewables are being added to growing fossil fuels capacity, not substituting for it. The myth denies that most of the world’s energy consumption still comes from fossil fuels. Moreover, transnational corporations responsible for emissions are now co-opting concepts such as just energy transition to continue to profit from the looming crises, without taking serious responsibility for changing their energy sources.

In conclusion, the three categories presented paint a dark picture of the dominant trends in the energy transition. As Tatiana Roa Avendaño suggested, transition discourses do not question the capitalist, undemocratic and patriarchal character of the current energy model. For the panelists, there will be no democratic and just transition without questioning the ways our economy is based on fossil fuels and the way nature under capitalism is treated as a separate entity and a mere object of exploitation.

Energy and extractivism, complexities and pathways towards a just transition

In the second part of the discussion, the speakers reflected on strategies to advance alternative transitions from below. They expressed different perspectives and positionalities based on research, life and activist experiences, which allowed complementary ideas to emerge from the debates.

Art by Angie Vanessita for Oil Watch.

Tatiana Roa Avendaño introduced the proposal “leave the oil in the soil” advanced by OilWatch. This idea comes from indigenous ontologies that question instrumental rationality in the relationship with nature, and attribute other values to ecosystemic components. An example is the case of the U’wa community in Colombia, which mobilised against oil exploitation by the multinational Occidental Petroleum Company, arguing that oil is the blood of Mother Earth and should therefore remain in its sacred space. Such ontologies have led many communities to mobilise against extractive projects in Latin America, Africa, and other regions, in dialogue with other peasant and urban perspectives around local struggles for environmental justice and access to natural resources.

Similarly, proposals such as energy sovereignty, which is related to the idea of food sovereignty, emerge as an alternative for strengthening strategies for local energy production related to autonomous processes: a just transition of and for the people. This is the case of perspectives that seek to overcome the Nature/Society dichotomy, and those that seek to guarantee that production is directed towards sustaining life, rather than towards meeting the growing energy demands of extractive and industrial sectors. From these perspectives, alternative ontologies related to traditional agriculture emerge, which suggest that energy can be harvested from the sun, water and even from human beings through communal relationships. More broadly, grassroots organisations and movements have proposed new social paradigms around energy transition oriented towards what some have called the five Ds: de-power, de-privatise, de-centralize, de-concentrate and de-commodify. Roa Avendaño pointed to the importance of cross-sectoral organizing processes that bring together workers, indigenous people, educators, young people, women and environmentalists to advance this alternative energy transition, such as the Mesa Social Minero-Energética y Ambiental (Mining-Energy and Environmental Social Roundtable) and the Alianza Colombia Libre de Fracking (Fracking-Free Colombia Alliance).

These ideas were debated by Daniel Chavez, who recognized the relevance of local processes and grassroots initiatives that seek to strengthen collective management of energy, such as cooperatives. Nevertheless, he argued that the scale and urgency of the measures that ought to be taken to avoid the climate catastrophe provoked by fossil fuels must involve massive transformations in the global energy system, and for this, the state must play a leading role through the promotion of public ownership of energy. Efforts must be done to implement what he called “the public pathway: the radical shift to public and social ownership” in the setting of the failure of neoliberal and market-oriented approaches in the energy sector.

Report from TNI which analyzes the growing trend towards (re)municipalization of public services across the world, including energy. Source: TNI

Marina Weinberg proposed a shift in the discussion: While social mobilisation against extractivism is growing, many communities where extractive projects are being implemented have developed not only a material dependence on these activities but also an identity that allows them to recognise themselves collectively amid the exclusion. This is the case in northern Chile, which has been called a “genetically mining country”, with a long history of extraction of its enormous mineral deposits. This trap leads to an impossibility of thinking of less-harmful alternatives. Weinberg suggested that extractivism has worked in such profound ways that there is a cellular level on which it is installed, becoming a way of life and of national belonging. Consequently, any strategy towards an energy transition that aims to overcome extractivism must address this complexity, understanding its paradoxes and moving away from linear or univocal understandings of the problem, which goes much deeper than a change in the energy matrix and confronts the lack of alternative livelihood strategies.

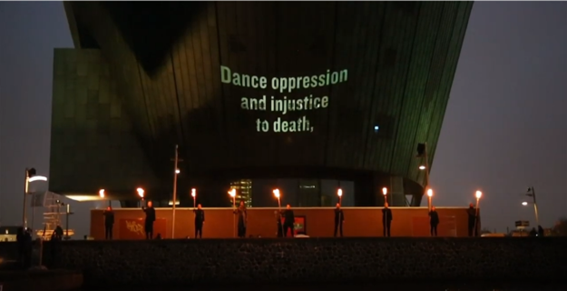

With this in mind, participants highlighted the relevance of art and culture in working on this cellular level of the global energy regime, which acts not only on communities living in extractive regions but also in the consumerism of everyday life in urban areas. Struggles against the ideological strategies that legitimize the global energy regime must use a pluriverse of resistance forms, including ceremonies, rituals, science and art to transform subjectivities, as Teresa Borasino suggested. As an example, Borasino showed a video of the performance “Keep Dancing” by Fossil Free NL, which memorialized at the NEMO Science Museum in Amsterdam in November 2020 the Ogoni Nine murdered in Nigeria for their resistance against Shell, while at the same time denouncing Shell “artwashing” through the sponsorship of museums and cultural institutions. She highlighted that alternative visions are already here, they have, lived for thousands of years in what the West calls the global South. What we need is to make those visions “affective”, and feelable, and to decolonize our ways of communicating, not only to show but to embody: vision speaks to the eyes, but we could also enact practices that attend to sounds, smells and flavors.

Still from the video of “Keep dancing” by FFC. The quote is from murdered Ogoni activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. Source: Youtube

The crucial role of the feminist movements in building new subjectivities and collective strategies was remarked by all the participants. The feminist movement has insisted that the personal is political, and that energy is life, it flows across bodies and subjectivities, and it helps to structure people and nations. Thus , for the energy transition to succeed, it must put life at the centre, recognizing the limits of the planet and our relationships of eco-dependence and interdependence.

Dancing the tragedy away

Before closing, Gustavo García-López introduced “This is not America“, a music videoproduced by Puerto Rican artist René Pérez, known as “Residente” (formerly in Calle 13). The video shows part of the history and tensions created by colonial extractivism in Latin America, and how, amid liberation struggles, the so-called docile colonised have been able to create spaces to “dance the tragedy away.” “But we are not docile, nor are we colonised: viva Puerto Rico libre! viva América Latina libre!”

An attentive silence took over the auditorium as the music video showed shocking images of streets turned into battlefields. Suddenly, the room was filled with images of tear gas and police repression, and of smoke from the burning Amazon rainforest, but also of the resistance of indigenous people, peasants, students, and neighbourhoods in Latin America, who insist on dancing the tragedy away. It was the best possible end to a discussion that addressed the darkest scenarios of colonial and patriarchal capitalism, but also the fight for a just transition towards a more equitable world centred on life.

After the appreciation of the video, a round of questions and interventions was opened to the audience. This was followed by an invitation to the Butterfly, the charming bar of the ISS, owned by Sandy, a friendly and charismatic woman who organised drinks and snacks to share an informal moment to continue the discussion and get to know each other in a convivial space. After such exciting discussions, which highlighted the importance of rebellion in the academic, political, and artistic spheres, the day could not end without a Latin American ritual. As night fell, the bar was taken over by the rhythms of cumbia, salsa, reggaeton and vallenato, leading the round table participants and other visitors to merge in a joyful ritual of dancing and singing for other possible worlds.

Sebastian Reyes-Bejarano is a PhD researcher at the Centre for Latin American Research and Documentation (CEDLA), University of Amsterdam, and a member of the project River Commons, at Wageningen University. His research focuses on conflicts around river landscape transformations in the setting of the current global environmental crisis, and alternative co-governance initiatives that emerge amid commoning processes developed by agrarian movements mobilized for environmental and water justice in the central Andes of Colombia.

Gustavo García López is a Researcher at the Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, and member of the editorial collective of Undisciplined Environments.

Diego Andreucci is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Barcelona, and a member of the editorial collective of Undisciplined Environments. @diegoandreucci

Cover image: Art “Selva vs Petróleo” by Angie Vanessita for Oil Watch.