By Gustavo García López

A decolonial future requires naming the interconnections between the climate crisis and imperialism, seen in dramatic North-South inequalities, extractivist policies, corporatocracy, and militarism; while simultaneously reimagining climate as part of struggles for making collective worlds of justice, freedom, and interdependence, caring for our shared commons, in common.

In his protest song against US imperialism in the late 1960s, Puerto Rican artist Roy Brown sang: “Fire, fire, the world is on fire / Fire, fire, the Yankees want fire”. From Puerto Rico and Chile to Vietnam and Guinea-Bissau, from Operation Condor in the Americas to the coups in Congo and Ghana, fires raged from independence struggles, military invasions, and dictatorships. Fifty years later, we speak again of a “world on fire” from the climate crisis, our common home burnt by fossil fuels; but also, in the words of the Abolitionist collective from the people making collective worlds of “justice, freedom, self-determination, and interdependence” (Abolitionist Collective).

The world has been on fire for a long time. Source: Youth Climate Strike

I want to reflect on the historical interconnections between these different worlds on fire—the fires of the climate crisis and of colonialism—and on what a decolonial climate future can look like. I will do this drawing on my experiences from the Caribbean islands of Boriken/Puerto Rico into which I was born, and in conversation with scholars and activists engaged in this reimagining. I want to think of climate justice as liberation struggles seeking to remake livable lives beyond colonial extractivism. That locates justice in relation to (is)land, sovereignty and commons-making: Caring for territories and our human and non-human families, democratically, equitably, freely.

These discussions relate to decolonizing the studies and praxis of environmental justice, ‘development’, disasters, and climate change, from diverse geographies. They involve interrogating post-extractive futures: “Who or what are the agents of a decolonial politics? What is the nature of their resistance, and their world-making?”, as put by Thea Riofrancos.

Decolonial words of justice as insurgent dignity

Art by Zapantera Negra (2014)

I am We / Power to the people. I speak with many who have come before me. I am here thanks to my parents, who taught me justice and love for soil and plants, my abuelas, to whom I pray for light, tías, primos, and all my ancestors, friends, mentors, who have accompanied me in this journey. I come expressing the sorrow, joy, anger and love from our home-islands, our Matria. I come inspired by the Zapatistas, whose Caravan for Life has arrived these days to Europe to “seek what makes us equal”, to “build bridges of dignity which join the five continents”, and to affirm we are still in rebellion. I come with the word as a flower which will not die, a word that came from the bottom of history and earth which can no longer be torn by the arrogance of power. As the rapper and teacher Luis Díaz aka Intifada sings: “I want to plant … this seed/ so it flowers in the land of the Coquí”.

I come thinking-feeling the contradictions of speaking about decolonization, while receiving an award created by a Prince, as a white-skinned ‘Latino’ man embracing Afro-Taino heritage [i]. I come knowing myself as colonized, but also as colonizer, wearing a “white innocence” mask. I come to speak truth to power, humbled by the many world-beings that have given life for justice and freedom, and the many networks of care and commons-making that sustain me. I am here thanks to Irina, intellectual partner, friend, instigator, carer, mother of our daughter Maia. I am here because of Maia, whose name means “Mountain”, “Mother”, “Magic”, “Love”, “Courage”. Maia who talks to trees to thank and protect them. She who has taught me so much in so little time about what matters most in this life—heart, care, truth—and to whom I owe the responsibility to give everything to help build a liveable future for all. I promise her “no one is going to devour us, to push this ocean over the Edge” (as Marshall Islands’ poet Kathy Jetñil-Kijner tells her daughter). I tell her, with the Zapatistas: “…For us joyful rebellion…For us insurgent dignity”.

Colonial climates: Killing us profitably

Colonialism institutionalized racism to justify accumulation of wealth and power. To remember this history is to purposefully take stock of the magnitude of colonial damage, in order to redress it. Memory is justice, nothing is complete without it, the Zapatistas remind us. Colonialism destroyed ancestral ways of life and knowing-being. It gave rise to the idea that all territories found across the globe were resource for the colonizers. It was a “veritable catastrophe”, a genocide and ecocide, which was entangled with the privatization of the global climate commons. This “co2onialism” persists to this day in many forms: in dramatic North-South inequalities, extractivist policies, corporatocracy, militarism. It is present across different sectors, from energy and toxic wastes to mining, agriculture and conservation, constituting ‘eco-imperial relations’.

We can see climate colonialism in the obscene climate inequalities between rich and poor. As the image shows, the richest 10% of the world’s people generate nearly 50% of all consumption-related greenhouse gas emissions, while the poorest 50% of the world —the ones most impacted by climate changes— generate only 10% of these emissions. Since the rise of industrial capitalism and imperialism, rich countries took as ‘loans’ the emissions of the future from the rest of the world, generating an ecological/climate debt, which add to the already existing colonial debts awaiting reparations. Because of these inequalities, the Anthropocene is not of all humanity: It is an “Anthro-Obscene” a “scandalous thing”, a “monstrosity”.

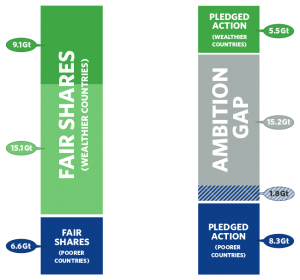

Ambition gap. Source: Civil Society Review

Climate colonialism is evident in international negotiations, where the richest countries have resisted binding emission reductions and climate reparations. In the Paris Agreement, the poorer countries have pledged more reductions than their fair shares, while the richer countries—the ones with more capacity and responsibility to act—have done the opposite. This substantial “ambition gap” in the reductions needed will deprive us of keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees. As the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance (PACJA) argued in the 2009 Copenhaguen Conference of the Parties (COP), this amounts to suicide. Thus we chant: “No to climate colonialism. No to climate genocide!”. This reminds of us of a longer history of similar crimes past and present, from toxic genocide against Native Americans, Brazilian Amazon’s indigenous genocide, to Campania’s biocide.

This climate genocide repeats the colonial logic of some regions being considered zones of extraction, of sacrifice and disposability, of subhumans. This is seen in the increasing numbers of environmental defenders killed every week, hundreds and growing every year, and the countless others silenced by threats: to destroy the forests, like Ze Claudio and Maria in Brazil; to build the dams, like Berta Caceres in Honduras; to extract the oil, like Ken Saro-Wiwa in Nigeria; to mine the lands, like Datu Kaylo Bontulan in The Philippines. These deaths become justified in the name of progress. The same logic repeated by Forbes magazine, celebrating how the current pandemic made so many new billionaires in 2021.

Fossil fuel corporations must pay for their crimes. Source: Platform London

Climate colonialism is in how 100 fossil corporations are responsible for 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions. In how Exxon makes more money in one financial quarter, than the entire GDP of dozens of Sub-Saharan nations. We see it in the environmental crimes of Exxon in Alaska, Shell in Nigeria, Chevron in Ecuador, Total in Mozambique, and many more. In the cancerous fossil fuel alleys from Louisiana and Navajo Land to Guayama, Puerto Rico and Ogoni Land. In the fact that these corporations knew and hid evidence of climate change for 50 years. In the deceit and double talk, publicly declaring support for climate action, while spending billions to bribe public officials to obstruct action and promote climate denialism, to greenwash their image, and make us feel it’s all our fault. We see the climate colonialism in how a black man is killed for being black, while these corporations face no accountability for what are no less than unprecedented crimes against humanity. We see this co2onialism in how governments, prime ministers and royal families own, subsidize and lobby for these corporations; while the major banks spend trillions financing them, even after the Paris Agreement. The same banks like JPMorgan-Chase that gamble, launder, defraud and blackmail to make a killing from highly-indebted countries such as Puerto Rico.

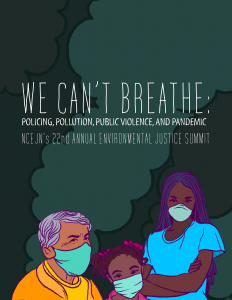

From police to corporate brutality, climate colonialism is in the many structures of racism that do not let us breathe. Source: North Carolina Environmental Justice Network

Climate colonialism is in the U.S. Military-Industrial complex. With hundreds of bases all over the world ready for invasion, it is the largest global consumer of petroleum and a major climate warmer. A military that facilitates controlling territories for extracting more fossil fuels in what has been called oil/petro/energy imperialism. The global climate footprint goes together with a “military bootprint”. The same geopolitical military logics are often present in disaster recovery processes; and we could speak about a “disaster authoritarianism” that accompanies such processes.

Climate genocide in the Caribbean: Disappearing sovereignty, disappearing islands

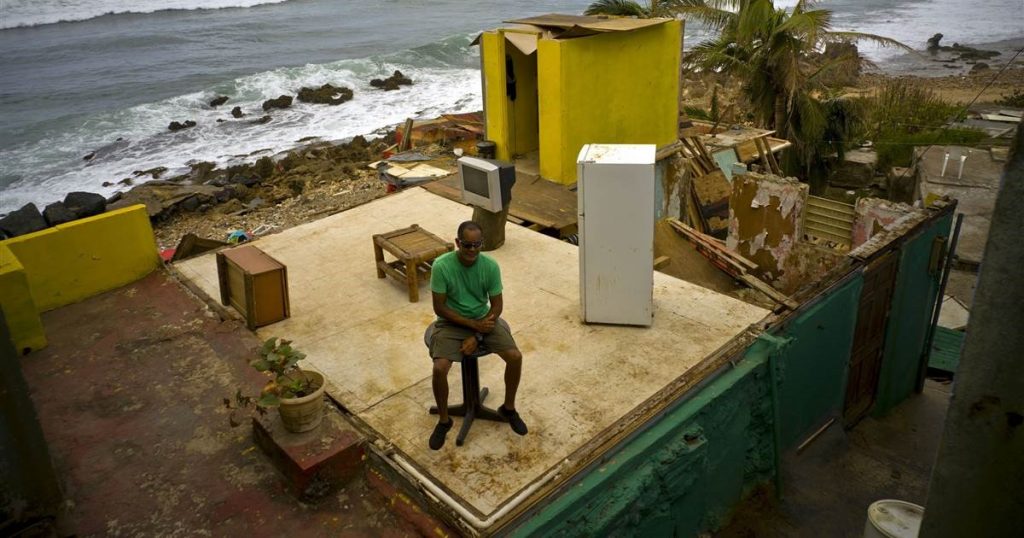

Man in his lost home after Maria. Source: N/A

Climate colonialism is deepest in the islands of the Caribbean and the Pacific. They are amongst the most impacted by the climate crisis, yet amongst the least sovereign, many remaining under the control of Northern countries. Our islands are seen as “remote and isolated”, depopulated, less important, “poor”; at the same time that they are subjected to intensive exploitation. Indeed, the Caribbean has always served as “pivotal space” in the geographies of “offshoring”: in the 20th century, the region had extensive investment in mining and refining of bauxite; ports, military bases and weapons testing ranges; and at one point was the world’s largest exporter of refined petroleum products, mostly for the United States. We see climate colonialism in the logic of “let them drown”, as islands disappear due to rising sea level, the same logic that pushes refugees to drown in the Mediterranean. The same logic that US Security Adviser Henry Kissinger used to justify the nuclear bombing in the Marshall Islands, when he said “who gives a damn” about so few people living there, and then won the Nobel Peace Prize.

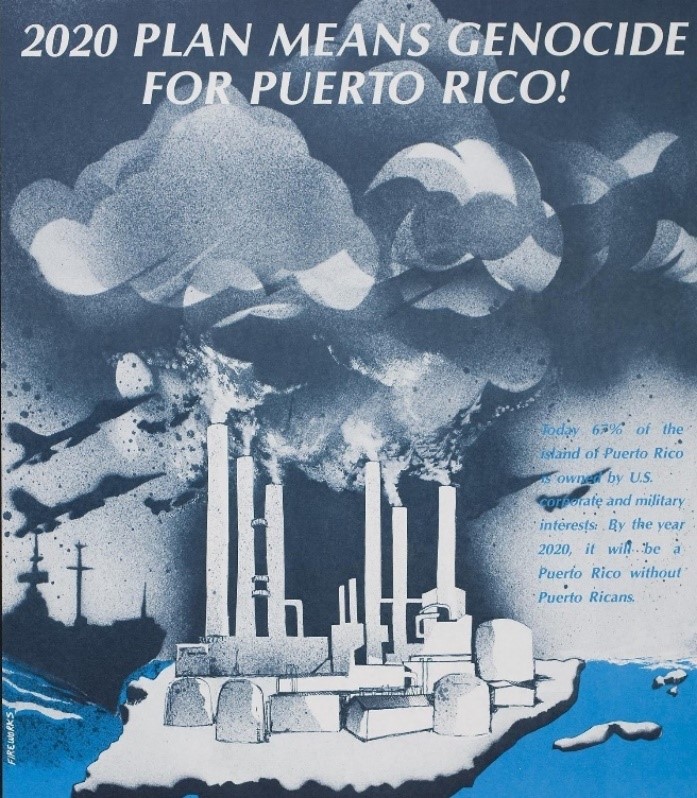

Solidarity campaign against the empire’s extractivist plans in Puerto Rico in the 1970s-1980s, officially dubbed Plan 2020. The text in the right hand emphasizes that 67% of the country owned by the US, and concludes that by 2020, it will be a “Puerto Rico without Puerto Ricans”. Art by Terry Forman, Fireworks Graphics Collective, 1983.

In Puerto Rico, this climate colonialism is seen in the plans for “free” zones for development that the US began in the 1960s, to turn us into the “showcase” for the rest of Latin America, for petrochemicals to refine the most toxic fuels, and for their military to train their armies and test their weapons, such as Agent Orange. A plan that, if fully executed, would mean genocide for Puerto Rico—similar to how they made Guam and the Marshall Islands practically uninhabitable. They justified it arguing we were too small, overpopulated, lacking resources or intelligence to be sovereign. We see climate colonialism in how they’ve continued with these plans ever since, abandoning the contaminated plants and bases while adding new ones: pharmaceuticals, transgenic crops, coal plants, proposed waste incinerators and methane gas infrastructure.

We felt climate colonialism with their $74+ billion dollar debt crisis generated by corruption and speculation; and the imposition of a Fiscal Control Board to impose austerity and make sure we pay it through vicious austerity. We felt it with hurricane Maria, which showed how impoverished, extracted, polluted territories become so deadly when facing climate disasters, especially for black, brown, and indigenous peoples. The same we saw with hurricanes Katrina in New Orleans, Irma in Barbuda, Dorian in the Bahamas, Iota in Nicaragua, Idai in Mozambique. We saw this colonialism in those who laughed at the 4,645 deaths from Hurricane Maria, and cheered the emptying of the country with the emigration of tens of thousands. We saw climate colonialism in how businesses and politicians use these tragedy as opportunities to make profit—pay illegal debts, award billions in contracts to corporate vultures, displace communities, and reduce and privatize essential services: health, schools, electricity.

Decolonial futures: Making climate commons

The colony is a disaster. / The disaster is the colony. Art by F. “Cesco” Lovascio di Santis through The Portrait-Story Project in collaboration with Proyecto de Apoyo Mutuo de Mariana, Humacao.

Yet, we also imagined and experimented with decolonial climate futures. As an imperative to “change everything”, decolonizing the climate means reimagining justice as freedom to nurture our commons—our coasts and oceans, our mountains and rivers, our energy, our food, our communities. Such a decolonial approach involves intersectional issues of self-determination, land/territory, class, and racial and gender justice. We, as the People, declared: No to the mines/to the gas pipeline/to the incinerator/to the AES coal plant, Yes to Forests/Water /Life—and we prevailed. After Maria, drawing on the deep insurgent legacies of our islands, we affirmed, “we don’t eat austerity”, “the disaster is the colony”, fist clenched in a sign of resistance. We joined forces with climate justice movements in the US and the Caribbean, to denounce this disaster capitalism. We understood that our struggles were a matter of life and death; and that making life in common meant interweaving (entretejer) movements for debt cancellation and reparations, for solidarity and self-management, food and energy sovereignty, and climate action now.

![Video] De los desastres del capitalismo al capitalismo del desastre: resistencias y alternativas – JunteGente](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/W0S3sV-xZgU/maxresdefault.jpg)

Art by José Primo Hernández of AgitArte/Papel Machete, originally titled “No Comemos Austeridad” (“We Don’t Eat Austerity”), adapted by AgitArte for forum “From the Disasters of Capitalism to Disaster Capitalism”, organized by Professors Self-Assembled in Solidary Resistance (PAReS) in collaboration with the US Climate Justice Alliance and The Intercept. Source: JunteGente.

People before the debt!” Protest in front of the US Federal Court in San Juan. Source: Center for Investigative Journalism

Making decolonial climate commons requires taxing and degrowing the rich, to reduce excess luxury emissions and allow space for livelihood emissions for all It requires the rich to pay their fair share to support adaptation, and redress the damages from colonial-climatic disasters transferring the wealth and decision-making power to the most impacted communities in the frontlines of the crisis, which are the ones most often #LeadingWithSolutions. This also means fighting for a debt #AuditNOW! and elimination of illegal debts, which cripple our ability to act. Feminist and anti-colonial movements show a new “pedagogy of the indebted”. They imagine “anti-debt futures”, with new agreements that put “people before the debt”, “make the banks pay”, “end corporate welfare”, and recognize the colonial debts owed to us. As put by Jubileo Sur/CADTM: “We do not owe. We are the creditors!”

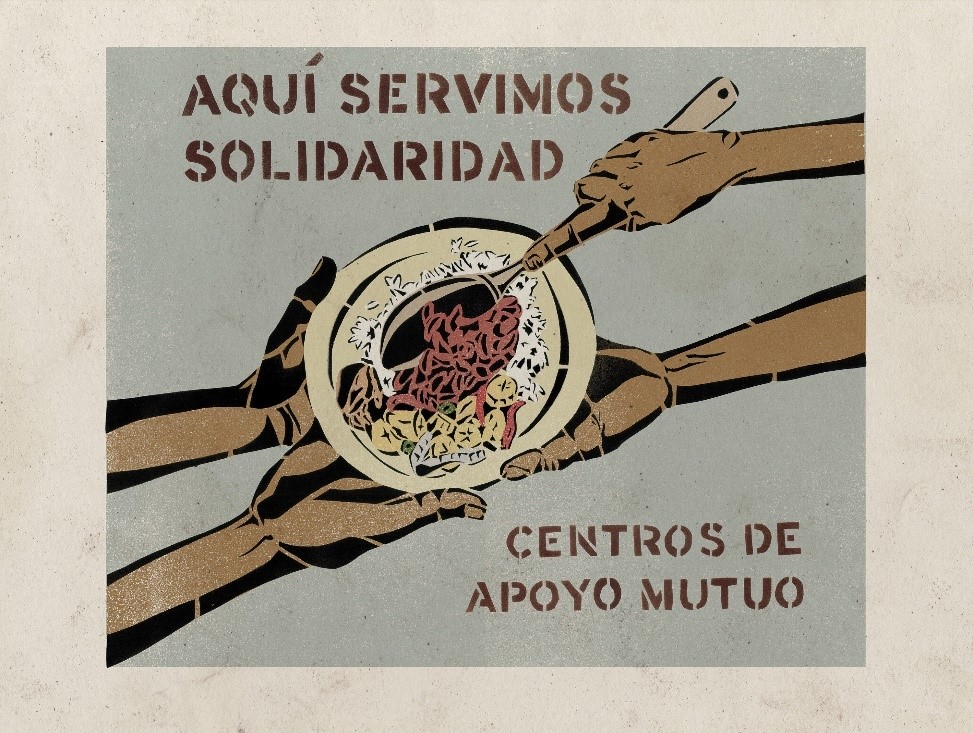

Here We Serve Solidarity. Centros de Apoyo Mutuo. Art by Javier Maldonado O’Farrill, AgitArte/Papel Machete. Source: AgitArte |

“Solo el pueblo salva el pueblo” / “Only the people save the people”. Decolonial climate futures demand that we build new relations and labours of care in common to reproduce life. We saw this after Maria in the dozens of mutual aid initiatives that prepared and shared food and other basic needs, helping clean up debris, “serving solidarity”, not charity. As the Mutual Aid Project in Mariana stated, these initiatives were “moved by happiness”, countering the sorrow from the government’s criminal negligence. Because, “in the fissures of crisis there is joy / for without it / there is death”, as put by poet Ana Portnoy. Taking sovereignty into our own hands, we learned that “community is our best chance at survival.” And that, in the process, we can move from despair to healing, and forge a new Puerto Rico: rebuild homes and mobilize for the right to housing and stay in place, expand agroecological farms for food sovereignty, develop new models of collective land ownership, and community energy.

“We are moved by happiness.” Source: Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo Mariana /Asociación Recreativa y Cultural de Mariana (ARECMA)

“March of the Sun: Adjuntas and Puerto Rico: Solar People/Solar Town”. Source: Casa Pueblo

Reconfiguring how we produce and consume energy is one of the urgent tasks for a decolonial climate future. Beyond the technical ‘fixes’ of solar panels and electric cars, this requires commoning energy. Organizations like Casa Pueblo (People’s House) in the central mountains, and the Jobos Bay Eco-Development Initiative (IDEBAJO) in the south coast, have led the movement to enact an equitable, democratic national solar energy transition. Against the government’s plans to continue fossil fuels slavery through new methane gas infrastructures, these movements have envisioned the Sun as key to “power life” and build an “energy future that is ours”. They have enacted community solar projects to address basic energy needs, provide local employment, and regenerate communal ties; but also to delink from energy colonialism, to create their own utopia of energy commons without waiting for change from above.

Activists denounce “An illegal contract/ LUMA wants to impose” and “LUMA wants to steal/ Our essential services”, while demanding #WeWantSun

Decolonial futures defend and reclaim essential services indispensable to the common good. In that sense, they also common the public sphere. We see this in the emerging movement against privatizing the energy system to LUMA, a consortium of two North American methane-gas infrastructure companies. Concerted resistance is emerging between environmental justice and climate action activists; labor organizations from electricity, education, and transport; and feminists against the debt and privatization, amongst others. They show how privatization is incompatible with a renewable energy transition, or with guaranteeing just recovery processes in future climate disasters. They denounce the stealing of our basic services through imposed illegal contracts. As put by Mariolga Reyes: “When they privatize everything, they will have deprived us from everything”. Drawing on the inspiration of the mass mobilizations that expelled the highly corrupt governor, Ricky Roselló, in the summer 2019, the movement promises to offer another “combative summer”. They remind us that, without justice, there will be no peace.

“It Takes Roots” Campaign by a coalition of environmental justice organizations in support just recovery / just transition. Source: Climate Justice Alliance

Decolonizing the climate means building commons movements that push for the necessary actions now to ensure livable, socially-just futures. Beyond the dominant discourse of emergency, which foresees only more crisis, we have found the hope and emergence of something new. We have learned to achieve together what we could not achieve separately, understanding that all our justice struggles—for education, for health, for housing, for food, for clean water, the sun, for anti-debt futures, for women and black liberation, for national sovereignty— are interconnected We have seen that #ItTakesRoots to Weather the Storm. We re-imagine just recovery as systemic changes, not climate changes: as building collective power, agency, self-determination. Because, as put by Anthony Rogers-Wright, “justice without power is impotent, and power without justice is tyranny.” We fight to transition from an extractive economy into a regenerative one, imagining new socio-ecological treaties for a “dignified future”. Decoloniality is a future full of creative and destructive possibilities, building island worlds in which we thrive, where “all that we have is what we owe to one another”, as Adriana Garriga-López, citing Fred Molten, says.

From Caribe to Palestine

To counter the repeated failures of international negotiations, a proliferation of multi-sited actions will be needed, from neighbourhood and municipal to national and transnational. We can imagine it as what Mimi Sheller calls “islanding”, a collective world-making that builds protection and healing for island-futures, and creates hope for “humanity as a global archipelago”. This takes us to our neighbors in the Dominican Republic, who fight against corruption, the expansion of coal infrastructures and their toxic ashes; to Haiti, confronting a military occupation and a crippling, extortionary debt; and Cuba, which despite a criminal blockade has been one of the leaders in climate adaptation and food sovereignty in the region. It takes us to Colombia, where we join arms against the crimes of Duque and coal mining, for universal basic incomes and a just energy transition. To Chile, with the Mapuche’s centuries-long struggles to recover their ancestral lands, and with the movement for a new constitution with the environment at its core. To Palestine, to Brazil’s own Gaza Strip, and all indigenous peoples longing to be free and in peace. To South Africa and the Pan African nations who advocate climate justice and reparations. To the Zapatista encounters and the movements sprouting across Europe, against the new Lithium rush in Portugal, for agroecology and food justice in Romania, for degrowth paths Beyond Shell in the Netherlands. May we continue to weave these futures together. May this Island-Earth be for all.

—

Gustavo García-López is Researcher at the Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, and the 2019-2021 Prince Claus Chair in Development and Equity at the International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague. He is a member of the Undisciplined Environments editorial collective.

This post is a slightly edited version of the Inaugural Lecture of the Prince Claus Chair, given by the author on June 10, 2021. The video of the lecture and a fully referenced version of this essay (with slight modifications in text) are available here.

Featured image (top): Climate and colonialism go together, the world has been on fire for 500 years of Co2onialism. Source: The Wretched of the Earth Collective

—

[i] I seek not to appropriate blackness, or tokenize deeply-rooted racial identities, nor to embrace the myth of ‘mixture of races’ that has predominated in Puerto Rico and has partly contributed to invisibilize racism. But I do feel and seek to inhabit a space beyond ‘whiteness’, which I embrace as a form of resistance to the US imperial project of whitening us and erasing our ancestral afro-indigenous island cultures. My experiences with racism, from being told I had ‘bad hair’, to being called a “spic” and told to shut up in England, to being shouted “go back to Iraq” in USA, have reinforced this non-Whiteness. I inhabit this space inspired by rapper Luis Diaz aka Intifada’s words, who points to the mixture and to our shared struggles for freedom: “I am a mixture like rum and anise / that you don’t have from Congo or Mozambique? / go to the mirror and search your nose / after all, if we see in deep (inside) the sea / there is a mutiny in our slave ship.” This space is marked by the Taino heritage, in our lands, their archaeologies and names, many words of our language, and our maternal blood lineages; by our West-African and Pan-Caribbean heritage, manifested in how bomba, plena, rumba and reggueaton music makes us vibrate to the core, fosters cultural Black affirmation, create encounters, and empowers a “great racialized Puerto Rican family” to mobilize, as Bárbara Abadía Rexach documents for the summer 2019 protests; and by Middle-Eastern and North-African heritage, in my proudly Afro hair, in my aunt’s and my cousin’s dark olive skin and thick black eyebrows, and in my Moroccan uncle “Sinbad the Traveler”, who made his life in Puerto Rico and inspired us with his passion for music in his radio show Marhaban.

Hermoso texto, hermosas imágenes. Gracias por este trabajo <3

Muchas gracias por la lectura y tu comentario Constanza, nos alegra mucho que te haya gustado! Att Gustavo, Undisciplined Environments Collective