by Amber Huff, Salima Tasdemir, and Patrick Huff

Today is a National Day of Action to #DefendAfrin, a city in Northern Syria (Rojava) which has been the center of both a brutal war and a remarkable and radical democratic experiment. This international call for solidarity seeks to continue to bring attention to the high stakes in Afrin, and to how the dynamics of power and resource grabs by the US and Russia and their alliances in the region have shaped contemporary struggles for life and democracy.

On 20 January, Turkey launched a brutal air and ground invasion of Afrin canton in Northern Syria. Turkey claims that the Orwellian-named ‘Operation Olive Branch’ is a fight against terrorism and an effort to secure Turkey’s borders. However, Afrin, one of the three founding cantons of the autonomous rural region in Northern Syria commonly called by the Kurdish name of Rojava, has been one of the most stable and peaceful regions in Syria since the state collapsed in 2012, and part of a radical experiment in decentralised democracy.

Seeing the invasion of Afrin in context

Some choose to see Turkey’s current aggression against Afrin as simply the next episode of violence associated with the Syrian civil war, while others choose to take Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan’s claims to be ridding regions bordering Turkey from militant threats at face value.

Instead, the attack on Afrin should be viewed in the context of the Turkish state’s long support of jihadist groups in opposition of the Assad regime in Syria and the intensification of a century of violent opposition towards any type of self-expression, self-rule or self-organization by Kurdish people; particularly the large Kurdish population living within Turkey who, the government fears, are emboldened by the existence of autonomous Kurdish regions on its borders.

Turkey-backed jihadist recruits destroy symbols of Kurdish resistance in Afrin city centre: Burning a Women’s Defense Unit (YPJ) flag and attempting to remove a statue of Kawa the Blacksmith, a legendary symbol of Kurdish struggle and survival. Source: Unknown.

The war in Afrin, viewed in wider context, starkly highlights how the crises and contradictions of the current political conjuncture, including those arising from the dynamics of power and resource grabs by the US and Russia and their alliances in the region, have shaped contemporary struggles for life and democracy.

In this case putting forces that represent systems of neo-imperial and extractive ‘capitalism, authoritarian statism, religious fundamentalism and in some cases pure fascism… in charge of establishing democracy and peace’ has opened spaces for new forms and manifestations of authoritarian populism to emerge or deepen their hold on society.

This has fueled the rise of the Islamic State and other jihadist groups, strengthened right-wing nationalism and given free-license for governments violently to suppress dissent and collective self-expression within their borders in the name of ‘fighting terrorism’.

Opening spaces for radical democracy

These contradictions can also open spaces for new alliances, philosophies and praxes of emancipation and resistance. Despite being surrounded by enemies on all sides, including hostile state actors, state-backed jihadist groups and Al Qaeda, Rojava has maintained its autonomy since the Movement for a Democratic Society (now the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria), a multi-ethnic multiparty coalition, rose in prominence in 2012.

These two WomenRiseUp images were created by members of the international solidarity movement for women’s day of action for Afrin.

This period has presented the world with a remarkable, radically democratic experiment amidst the wreckage wrought by the deadliest and most geopolitically complex war of the 21st century, and its lessons are influencing debates and movements around radical alternatives around the world. In 2014 Rojava’s three cantons, Afrin, Kobanî and Jazira, united under ‘The Charter of the Social Contract’. This formed the basis for the implementation of a new form of non-statist governance called democratic confederalism, based on ‘bottom-up’ confederated democracy, religious and ethnic pluralism, ecological society, and substantive women’s liberation.

So what has been accomplished in practice? In Afrin, as across Rojava, democratic confederalism is based on the idea that society can be run truly democratically when power rests with the people rather than with state bureaucracies. The basis of governance is a network of inclusive, community-level assemblies or communes that are the primary locus of decision-making across sectors from sanitation to economy to education. Local assemblies, through elected representatives, form confederations across cities and regions that coordinate to implement decisions. This system includes a mandate of co-chairmanship at every level as a mechanism to ensure ethnic and gender pluralism in decision-making as well as to prevent individuals from consolidating power over communes or at higher levels.

In Rojava and neighbouring Bakur (the part of Kurdistan located within the borders of Turkey) co-operatives are playing a key role in reshaping the ravaged economy of the region, with immediate goals of meeting people’s basic household needs and controlling dramatic price fluctuations resulting from price-gouging and monopolies, and long-term goals towards sustainability and self-sufficiency.

Foremost, what is often simply called the ‘Women’s Revolution’, which aims to restructure the ways that patriarchy has shaped society and individuals, is an overarching driving force behind democratic confederalism’s radical democratic transformations.

YPJ (Women’s Protection Units) fighters in Afrin, February 2018. Source: Kurdishstruggle [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Defending autonomy and democracy

Self-defence has been crucial to the preservation of life and gradual institution and evolution of democratic confederalism in Rojava, as liberating the region from the brutal threat of the Islamic State and defending populations against cross-border attacks by the Turkish military and Syrian- and Turkey-backed jihadist militias have been necessary. While the YPG (People’s Protection Units) and YPJ (Women’s Protection Units) have been a key part of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), tactically allied with the US military to eliminate the Islamic State, defence from other threats have fallen exclusively to the YPG and YPJ.

It is this reality and necessity of self-defence that is being twisted and mobilised by the Turkish state as justification for the bloody invasion of Afrin Canton. In Erdoğan’s framing, securing Turkey’s borders from ‘terrorism’ means carving out a 30-kilometer ‘safe zone’ across the border of a neighbouring country, eradicating the YPG, YPJ and that which they defend, putting countless civilians, including hundreds of thousands of refugees already displaced by violence elsewhere in Syria, at risk of further displacement, injury and death.

A demonstration in the city of Afrin, Syria in support of the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) against the Turkish military operation against the Afrin Region. 19 January 2018. Source: Voice of America Kurdish

An autonomous ‘Kurdish’ experiment in revolutionary democracy is at stark odds with the authoritarian, ultra-nationalist and anti-Kurdish discourse that has intensified in Turkey and enacted since the last general elections in 2016. This has included a shocking constitutional referendum that transformed Turkey from a parliamentary democracy to a presidential republic, with consolidated power in the executive; numerous acts of violence against ethnic minority groups in Turkey; the arrest and detention of elected MPs from the left-leaning and pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) and suppression of journalists and academics critical of the state.

It is little surprise that the aggression against Afrin, and by association, Rojava, comes just in time to shore up popular support inside Turkey for Erdoğan’s re-election as president in 2019.

High stakes

International calls for solidarity and a wave of demonstrations across the world have brought attention to the high stakes in Afrin, though the media has been slow to follow suit. Although the offensive has just begun, civilian deaths and injuries climb, and as many as 30,000 people have been displaced from border communities since the invasion began. As is always the case, the most vulnerable members of society are most at risk.

At stake, not least, and deserving of our attention and solidarity is a radical alternative to both violent authoritarian nationalism and broader systemic violence associated with the contradictory nexus of blind elite cosmopolitanism, neo-imperialism and intensifying militarization that drives uneven globalization.

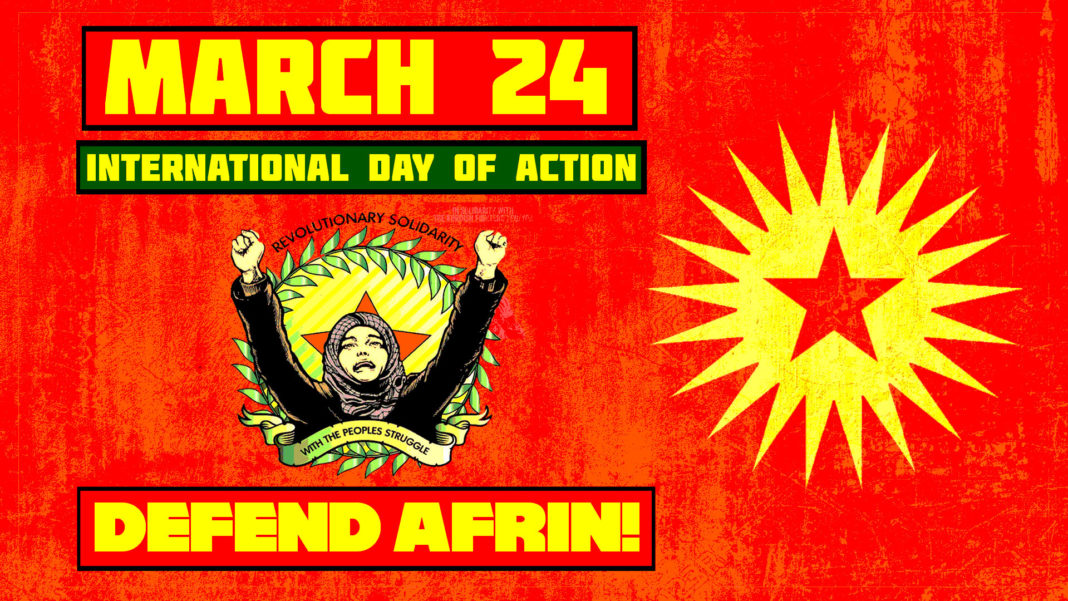

A number of groups are calling for a day of international solidarity with Afrin on Saturday, 24 March.

As Dilar Dirik, an activist in the Kurdish Women’s Movement, recently wrote, the war in Afrin ‘symbolizes two options that the peoples and communities of the Middle East face today: between militarist, patriarchal, fascist dictatorships on the one hand, controlled by foreign imperialist interests and capital, or the solidarity between autonomous, self-determined, free and equal communities on the other’.

Update (20 March 2018)

This piece was originally published on openDemocracy on 12 February 2018, as part of a series commissioned for the Emancipatory Rural Politics Initiative. Since then, a lot has happened. For nearly two months, a few thousand lightly armed members of the SDF, YPG and YPJ have confronted and resisted an invasion by NATO’s second largest military power. In recent weeks the invasion has in involved both intensifying direct and strategic targeting of civilians and vulnerable populations and near-silence from the international community. Afrin’s water supply was cut off and its main hospital was bombed. Aerial bombardment and shelling, and atrocities committed by Turkish troops and Turkish-backed forces on the ground, have resulted in hundreds of civilian deaths in the city. Early Sunday, news began to circulate on social media alongside claims by Erdoğan that the city centre of Afrin had been taken, the ‘terrorists’ were on the run, and that the flags of Turkey and their jihadist auxiliaries had been raised in the city. News trickled out from other sources that the SDF, YPG and YPJ had withdrawn to regroup and prevent the further massacre of civilians. The retreat from Afrin is not the end, but rather marks a new phase and a shift from direct confrontation to guerrilla resistance. As Othman Sheikh Issa, co-chair of the Afrin executive council, said recently in a televised statement, ‘Our forces all over Afrin will become a constant nightmare for them’.

Amber Huff is a Research Fellow in Resource Politics at the Institute of Development Studies, a member of the ESRC STEPS Centre, and a member of the UK Kurdistan Solidarity movement. Email: a.huff@ids.ac.uk

Salima Tasdemir is an activist and postdoctoral researcher in Gender Studies at the Centre for Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex. She is the Coordinator of the Sussex Kurdish Community Association. Email: salimatasdemir@gmail.com

Patrick Huff is an Associate Lecturer in Birkbeck’s Department of Geography, Environment and Development Studies. He studies social movements with a focus on anarchism and other forms of radical politics. He is a member the UK Kurdistan Solidarity movement. Email: pathuff123@gmail.com

Reblogged this on Political Ecology Network.

‘The retreat from Afrin is not the end, but rather marks a new phase…’

long live the amazing kurdish people!